Listen to Cody Levine, Ecologist for Worcestershire County Council, talking about how the Southern Link Road project reduced its impact on local wildlife and habitats (recorded 2021).

Wetland landscape

The land in front of you is a flood plain, an iron rich wetland where the Rivers Teme and Severn join. These rivers create important wildlife corridors, with streams joining up to support the movement of wildlife. Flooding is also a major part of the local story, as flood plains take water away from settlements like Worcester, providing a natural solution to flooding. This create a wetland landscape that riverine wildlife can call home.

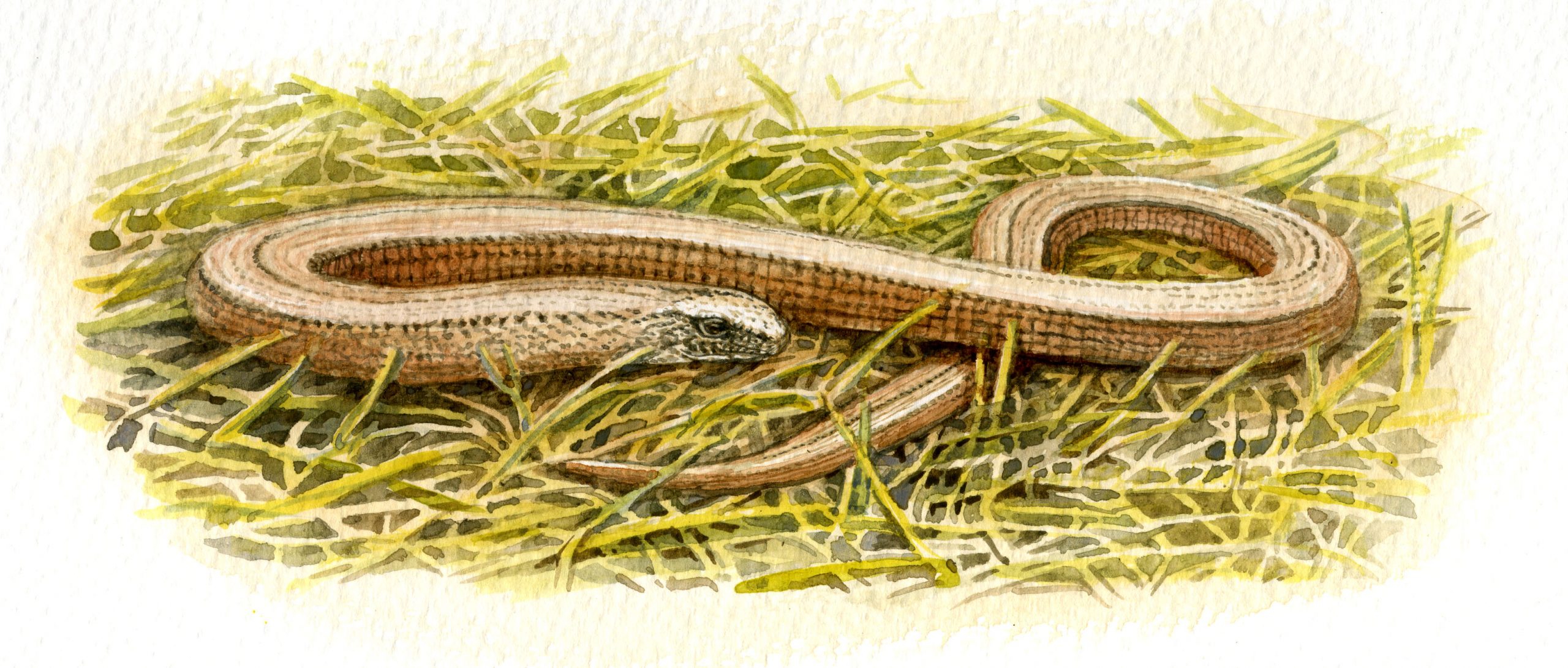

The land around Powick Hams contains badgers (Meles meles), otters (Lutra lutra), salmon (Salmo salar), trout (Salmo trutta), shad (Alosa sp), bats (Chiroptera sp), grass snake (Natrix natrix) and slow worms (Anguis fragilis), amongst many other fascinating species. For most of the year the land is also used to graze sheep and cattle.

Slow worm by Ian Gibson

Black Poplar near the Southern Link Road, by Ian Gibson

Some of the trees within the local landscape are over 100 years old and provide an important habitat for many creatures. One tree that stands out is a Black Poplar (Populus nigra), by Powick roundabout. Black Poplar is a ‘priority species’ within Worcestershire Biodiversity Action Plan and this particular tree was carefully protected during the construction of the original roundabout. Once there would have many Black Poplars on the banks of the local rivers, but today it is a rare example. The oldest tree in this landscape is an oak, which is thought to be around 300 years old.

Birds of prey, including barn owls (Tyto alba) and peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus) which nest at Worcester Cathedral, hunt over the open ground. Slow worms (a legless lizard) can be found on the north riverbank, which is an important discovery. Worcestershire, and Worcester City in particular, is thought to be a nationally important ‘hotspot’ for this particular Biodiversity Action Plan species.

Opportunity to enhance the environment

With the project to build a new bridge being within an important landscape, a major part of the planning revolved around the environment impact. Ecologists were involved to ensure that the impact on wildlife was minimised, and that where land or trees would be lost they would be appropriately replaced. The project was one the first schemes to demonstrate Biodiversity Net Gain – making sure the end result was measurably better for wildlife than before the work began.

What happened?

To protect existing trees, fences were erected around some of them to ensure no accidental damage and water was brushed away from the root system. Inevitably, some vegetation and trees had to go as part of the project. To replace the secondary woodland that was lost, new trees were planted. Native trees were chosen, including disease resistant Elm (Ulmus procera) that would support local wildlife. Quick and thick growing species were planted to establish a canopy of vegetation quickly.

Badger, by Ian Gibson

Since the loss of vegetation also meant loss of nesting sites, replacement bird and bat boxes were installed, included a barn owl box. Replacement badger setts were also built. Wildflower seeding took place on verges to support the local insect population.

Visible benefits

Building the bridge meant that some of the flood plain was lost. Since it was a priority to ensure net environmental gain – that the end result was better than at the start – a 4 hectare flood compensation area was excavated and seeded nearby. This is already attracting birds and importantly it is used by rare winter and passing waterfowl, such as curlew (Numenius arquata), oystercatchers (Haematopus ostralegus) and lapwings(Vanellus vanellus). The newly created wetland habitat is important for a diversity of rare flora and fauna, as well as being important in its own right as a priority habitat for conservation in Worcestershire; an estimated 40% of the UK’s wet grassland was lost between the 1930s and the 1980s and what remains is now particularly vulnerable to loss.

Lesser Horseshoe bat, by Ian Gibson

Bat corridor

At Powick Hams, lighting was designed to be sympathetic to wildlife, including the rare species of bats present. This is a corridor used by Lesser Horseshoe bats, the same species found roosting near Worcester Cathedral. They are a nationally rare species and particularly sensitive to artificial light, so lighting along the road is designed to be low level, make use of warmer colours and minimise spill.