Uncovering Roman activity on the Severn Estuary

Between August 2021 and October 2022, our archaeologists stripped back over 4.5 hectares of pastureland south of Pilning, South Gloucestershire. Working in all weathers, they recorded the remains of Romano-British activity that had been sealed beneath centuries of flood deposits.

Map showing the site’s location in relation to the Severn Estuary and Bristol

The site is now in the final stages of a long post-excavation process, that involves detailed analysis of the finds (including over 9900 sherds of pottery) and other specialist work before being collated into a final report. This online exhibition explores some of the early discoveries.

Before the Romans

The excavation revealed dark peat layers and blue-grey tidal clays, the natural Wentlooge Formation. These deposits formed long before the Romans, when the Severn Estuary’s salt marshes flooded and drained in seasonal cycles.

No prehistoric tools or structures were found, but the environmental layers uncovered tell us the land was a rich resource for grazing and fishing. In effect, the excavation gave archaeologists a cross-section of thousands of years of landscape change before human settlement began on the site.

Drone shot showing part of the excavation area with the Severn Estuary in the background

Roman times

When the Roman army arrived in Britain in AD 43, they reshaped both towns and countryside. Around Bristol and South Gloucestershire, activity focused on Abona (Sea Mills), a fort turned trading settlement on the River Avon, and on small farmsteads connected by new roads, including one passing near Pilning. Unlike great centres such as Cirencester or Gloucester, this area remained more rural, but it still formed part of the wider Roman world of roads, trade, and agriculture.

Roman activity on the site can be divided into two phases, the earliest being in the 1st-2nd century AD where a series of gullies and potential animal pens were uncovered. The excavation recovered calf, lamb, and foal remains which hint that this was not just pasture, but a working farm where animals were bred and reared.

During the second phase from the 2nd to 4th centuries AD, large-scale land reclamation occurred. To achieve this large parallel ditches and a long central trackway were built, forming part of a planned drainage system that extended beyond the limits of the dig.

Early evidence suggests that very little activity took place on the site after the end of the Roman period, probably due in part to the land become more waterlogged and making farming difficult. The team discovered a number of features covered by a blue-grey clay that appears to have formed during flooding in the later 4th century or beyond. Ironically, the same clay that ended the activity also protected its remains, preserving them until their rediscovery in 2021–22.

The Finds

Archaeologists uncovered plenty of exciting finds. Among the most striking were ditches packed with Roman pottery – hundreds of sherds from tankards, jars, and even near-complete vessels deliberately thrown away. Enclosure ditches were convenient dumping grounds, filled with the everyday tableware and storage jars. Far from rubbish alone, these deposits reveal the rhythms of domestic life: what people ate and drank from, how they stored their food, and how changing styles show the passing of time on a busy Romano-British site.

Ditch filled with large grey pottery sherds (50cm scale)

Click through the drop downs to find out about some of the exciting finds:

One of the smallest finds was a rare glass intaglio, crafted from layered blue and black glass to imitate semi-precious agate. Though modest in quality, it depicts a vigorous heroic figure, likely the Greek warrior Diomedes, famed for stealing the Palladium (a wooden statue which protected the city of Troy) during the Trojan War – the legendary conflict between the Greeks and the city of Troy.

Small glass intaglio that depicts a hero

This small gem would once have been set into a ring, serving both as a personal adornment and as a seal. Its imagery reflects the spread of classical myths into Roman Britain, where even on the Severn Estuary, people wore and used objects resonating with the stories of gods and heroes.

Turns out the Romans like beans too, as we uncovered the smashed remains of a burnished grey ware pot that still contained an abundance of charred Celtic beans (Vicia faba). The vessel was recovered from a mid- to later-Roman drainage ditch and dates to around the 3rd century AD.

Fragments of the pot in which beans were found.

This remarkable discovery provides a rare glimpse into everyday food practices in Roman Britain. The survival of both pot and crop, preserved by charring, offers direct evidence of diet, farming, and storage methods. The small portable nature of the pot containing the beans has us wondering… is this the Roman equivalent of a baked bean tin? However, someone clearly left these ones over a fire for too long!

The charred remains of beans – around 467 in total

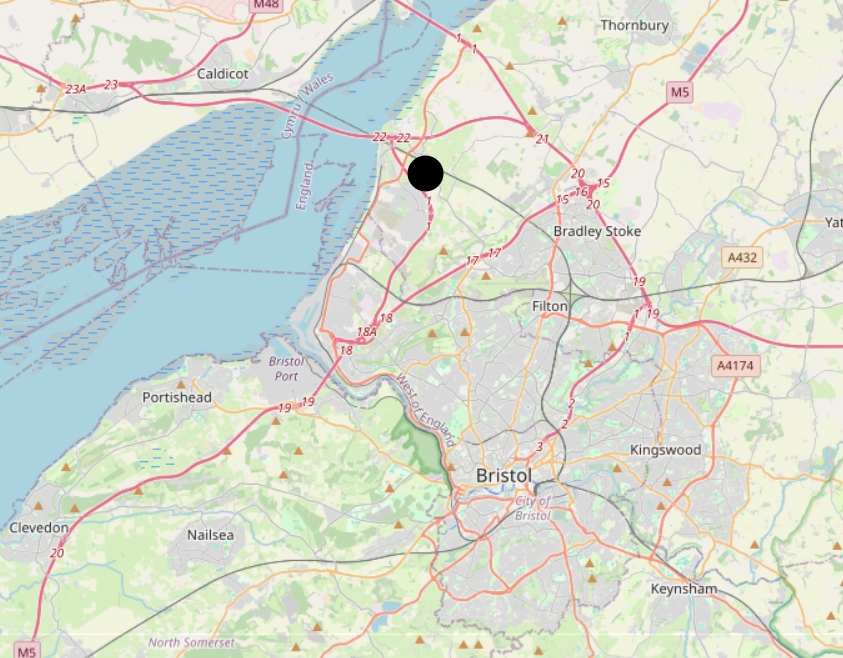

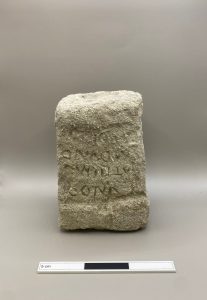

One of the star finds was an altar stone, which are uncommon outside of towns and forts. This altar links Pilning to the wider world of Roman religion and landholding, showing how communities on the empire’s edge engaged with shared traditions in their own ways.

Altar stone

The small carved altar, dating to the 4th century AD, was uncovered in the fill of a late Roman enclosure ditch. At first mistaken for a building fragment, careful cleaning revealed four worn lines of Latin lettering.

The inscription, though abbreviated and eroded, may refer to Moridunum (“sea-fort”) and to a landowner named Attius or Ateius. Portable altars like this could be dedicated in small shrines and easily moved between sites.

Though originally created for worship, the stone was later reused, perhaps as a boundary marker. Its discovery near a crouched burial hints that it may still have held symbolic meaning when deposited.

Get a closer look at the Altar Stone using our 3-D model

Keep an eye on this online exhibition over the next few months as we learn more about the site during the final stages of analysis.

Acknowledgements