Excavating Wolverhampton’s Old Hall

Explore the archaeology of a moated Elizabethan hall turned japanning factory in Wolverhampton

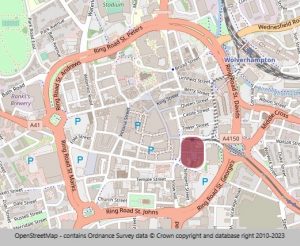

This exhibition shares the stories and highlights of archaeological excavations on the former site of Wolverhampton’s Old Hall in 2020-21, prior to the construction of the new City Learning Quarter (CLQ).

Discover how the site’s story changed along with society’s fashion for grand country houses, followed by the rise of industry then growth of schools for all. This is a tale of one site, but it encapsulates the rise of Wolverhampton as a major centre within the West Midlands.

Map of Wolverhampton city centre showing excavation site in red

A brief history of the site

Early days

Japanning works

Favourite finds

Want to know more?

A brief history of the site

Find out more about the documented history of the site by clicking on the side arrows to scroll through the timeline below.

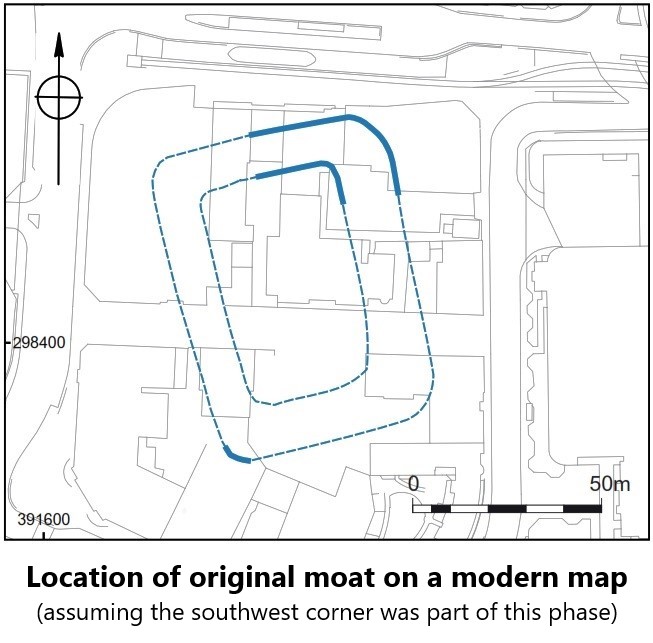

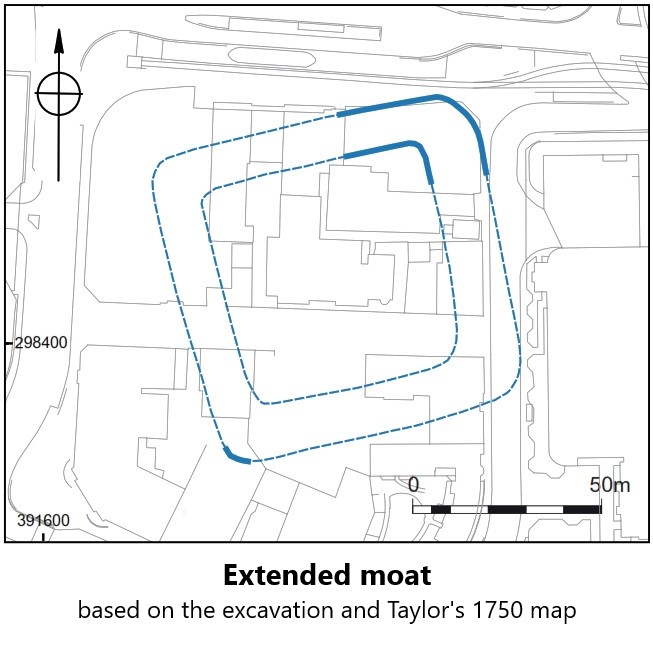

Early days: moated house

Old Hall (also known as Great Hall and Turton’s Hall) may have begun life as a medieval timber framed building. However, the first house we have evidence for was built by the Leveson family in the mid-late 1500s, during the Elizabethan era. A deep moat filled with water existed at this time too. Later on, the east side of the moat was backfilled and extended, probably by the Turton family in the early 1700s. A map from 1750 shows that the moat contained a garden and orchard with the house in the northwest corner.

Click on the side arrows to scroll through excavation images of the moat below and to see how the moat changed over time.

Excavating the moat

Two areas were excavated in 2020-21: Area 1 in the northeast corner of the site and Area 2 to the southwest. What we know about the moat mostly comes from Area 1 (as Area 2 lay outside it) and earlier excavation by Birmingham Archaeology in 2000-2003 and 2007.

Drag the slider to compare a modern map, marked with the excavation areas, to a 1750 map of Wolverhampton.

Below is an aerial photo of Area 1, with the original and extended arms of the moat marked in blue and the later curtain wall in red. A series of brick and stone wall lie on top of the moat. These are the remains of a Victorian school, built after the hall had been demolished and moat filled in.

Click on the ? symbols to find out more about the moat and key finds.

Want to explore further? You can step right into the excavation with a 3D model of the original moat where it’s crossed by the later curtain wall. The model will open in a new tab on the Sketchfab website – to move around the model, click and hold to drag, or scroll (pinch on mobile devices) to zoom in and out.

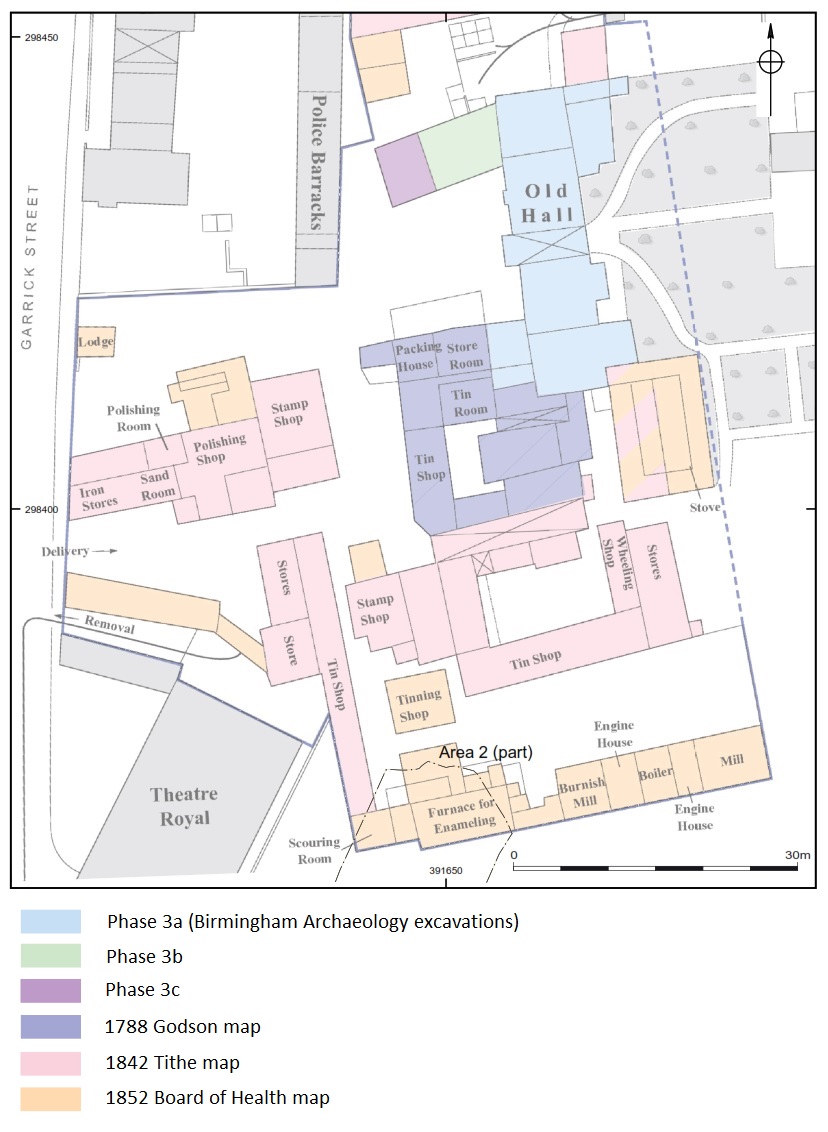

Japanning works

During the second half of the 18th century, the site (now known as the ‘Old Hall’) became a japanning factory. Japanning was an important trade in the West Midlands during the 18th and 19th centuries. Wolverhampton and nearby Bilston were at the centre of this thriving industry: at its height the trade employed over 2000 people locally.

Under the management of a succession of local firms; Jones and Taylor, Obadiah and William Ryton, Ryton and Walton, Benjamin Walton and Co, and finally Frederick Walton and Co the Old Hall Works grew to be one of the largest factories in the area. During the time of Benjamin Walton & Co (formed 1840) the highly popular ‘Wolverhampton Style’ – featuring painted scenes of castles, churches and well known houses on a bronze or gold background – developed at the Old Hall Works. This lasted until the industry began to decline in the later 19th century. Old Hall was eventually demolished in 1883.

Japanning was a popular decorative technique in the 18th and 19th centuries. It was inspired by East Asian lacquer work, which used sap from the Chinese lacquer tree (Toxicodendron vernicifluum). As this wasn’t available outside Asia, European firms imitated the glossy effect with resin based varnishes. Japanning was often used on furniture, as well as small metal items such as the kettle below, which dates from 1830-1860.

Bronchitis kettle, japanned metal, Lowe, 1830-1860

Science Museum Group

© The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0

William Highfield Jones, a future Mayor of Wolverhampton, was an apprentice at the Old Hall in 1839 and published his memories of the building. He remembers:

‘It had the appearance of a decayed Elizabethan mansion, with large square mullioned windows, a square tower in front over the entrance porch containing a large bell which was rung to summon people to work. Before the Hall stretched a large green paddock surrounded by a high wall and iron gates; a broad pathway led through the green paddock to the porch. Beyond the Hall was a nicely kept garden laid out with flower beds and fishponds filled with goldfish.’

Uncovering the factory

Below is an aerial photo of Area 2, which uncovered part of Old Hall Works. The furnace room, scouring room and a mystery range of buildings are highlighted in blue, three furnace rebuilds are shown in yellow, orange and red and a coal store is marked in grey.

Area 2 shown on a map of Old Hall Works, combining information from 1788, 1842 and 1852 maps and excavations by Birmingham Archaeology

Click on the ? symbols to find out more about the archaeology.

Want to explore further? Take a look at a 3D model of Area 2! This is a photogrammetry model created from hundreds of photographs. It will open in a new tab on the Sketchfab website – to move around the model, click and hold to drag, or scroll (pinch on mobile devices) to zoom in and out.

Favourite finds

A wide range of artefacts were found during the excavation – everything from fruit stones and shoes, to industrial waste and medieval pottery.

Click on the ? symbols to explore the selection of finds.

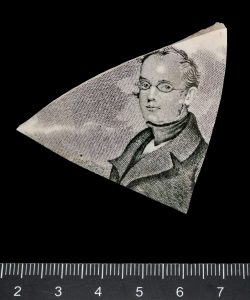

Sherd of pottery with the portrait of Joseph Rayner Stephens

The identity of the person depicted on this pot sherd was originally a mystery, as he doesn’t appear on any well know designs. However, thanks to the power of social media we have been able to establish that it is a likeness of Joseph Rayner Stephens (8 March 1805 – 18 February 1879).

Joseph was a somewhat controversial figure, a Methodist minister based in Manchester and then Ashton-under-Lyne, who was actively involved with the Chartist movement of the mid 19th century. He addressed Chartist meetings and even went to prison in 1838. Contemporary sources tell us that he was a charismatic speaker, so is likely to have been quite well known during his day as a champion of the poor.

We have not yet found a direct link between him and Wolverhampton, but this discovery – on the site of a contemporary factory – is of interest and hints at support for the Chartist cause in the area.

For further information on Joseph Rayner Stephens, visit Rayner Stephens – Wikipedia

Odo-ro-no bottle found during the excavation

This little bottle tells a big story – how the public became convinced that body odour was unnatural and problematic.

In the early 1900s, it was generally thought that it was unnecessary and potentially unhealthy to stop sweating. Those bothered by bad smelling body odours dealt with it by washing often, perfume and clothes shields (extra layers of absorbent fabric in the underarms of clothes). So when Odo-ro-no came along the sellers had a hard time convincing people that they needed it. Originally invented by a Cincinnati doctor, Abraham Murphey, for stopping his hands sweating during surgery, it was taken up by his daugther Edna as a general antiperspirant.

Odo-ro-no was a red liquid that to be applied 2-3 evenings a week (so that it had time to dry overnight). It was powerful stuff: 33% aluminium chloride and contact with sweat produced hydrochloric acid, among other substances. The result was skin irritation and even cases of skin ulcers.

1919 ‘whisper-copy’ advert for Odo-ro-no by James Young entitled “What you hesitate to tell your dearest friend”

So, how did Odo-ro-no convince Americans and later the wider world, that they needed such antiperspirant?

Advertising and invented social pressure. Adverts specifically targeted women and planted the idea that they smelt bad, but everyone was too polite to say, and that body odour was at the root of their social problems or a lack of suitors. It worked, sales soared and this style of ‘whisper-copy’ advertising (implying there was a problem no one talked about) went from being shocking to being much copied.

Want to know more?

- For more detail about the archaeological excavation, features and finds take a look at the CLQ excavation report.

- An account of Birmingham Archaeology’s earlier excavations can be found in an article on Wolverhampton’s Local History website Old Hall excavations 2002. A full report of the 2000-2007 excavations – Great Hall, Wolverhampton: Elizabethan Mansion to Victorian Workshop – is also available from the City Archive’s Local Studies Library or to buy from BAR Publishing.

- Further information on The Old Hall Works, the recollections of William Highfield Jones and japanning in Wolverhampton can be found here: Old Hall Japanning Works – Wolverhampton History and The Great Hall by Michael Shaw.

- To discover more archaeology and historic sites in Wolverhampton, take a look at the city’s Historic Environment Record (HER). This ties all recorded information to a modern map of the area.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to City of Wolverhampton Council and Turner & Townsend for commissioning this online exhibition. It was created by Worcestershire Archaeology’s outreach team as part of archaeological work prior to the construction of the City Learning Quarter. All images belong to Worcestershire Archaeology unless otherwise stated.