From Hester Pengelly to Charles Darwin

- 20th August 2025

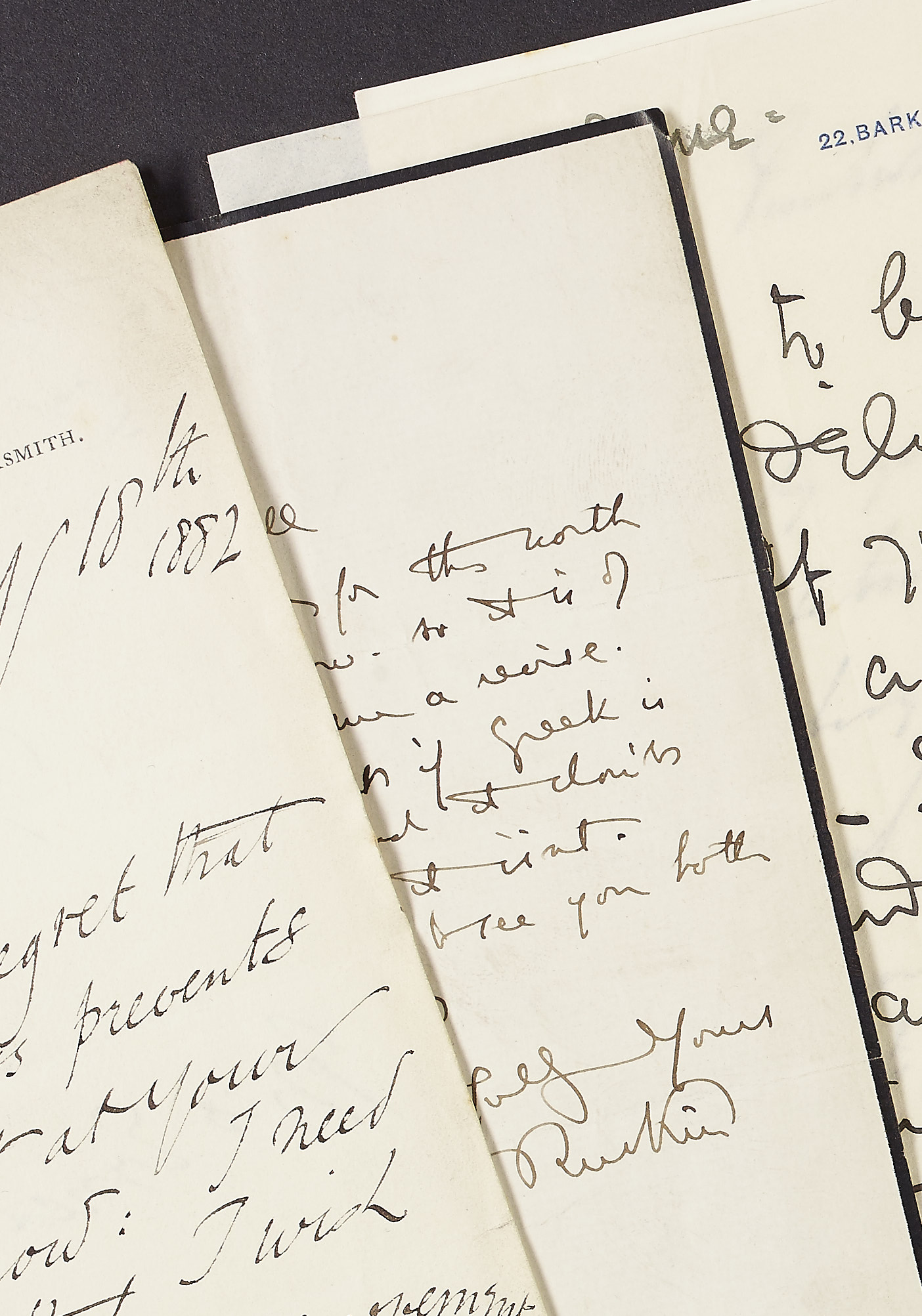

A recent deposit of material with connections to the Binyon and Spriggs family of Henwick Grove, Worcester has revealed a remarkable set of letters from well-known scientists, government officials and artists of the 19th century, including Charles Darwin (and with some irony, his most celebrated opponent and creator of the London Natural History Museum, Sir. Richard Owen). With the help of the Darwin Correspondence Project (DCP) and some detective work we learn what the letter can tell us about Darwin’s life and work at the time of writing.

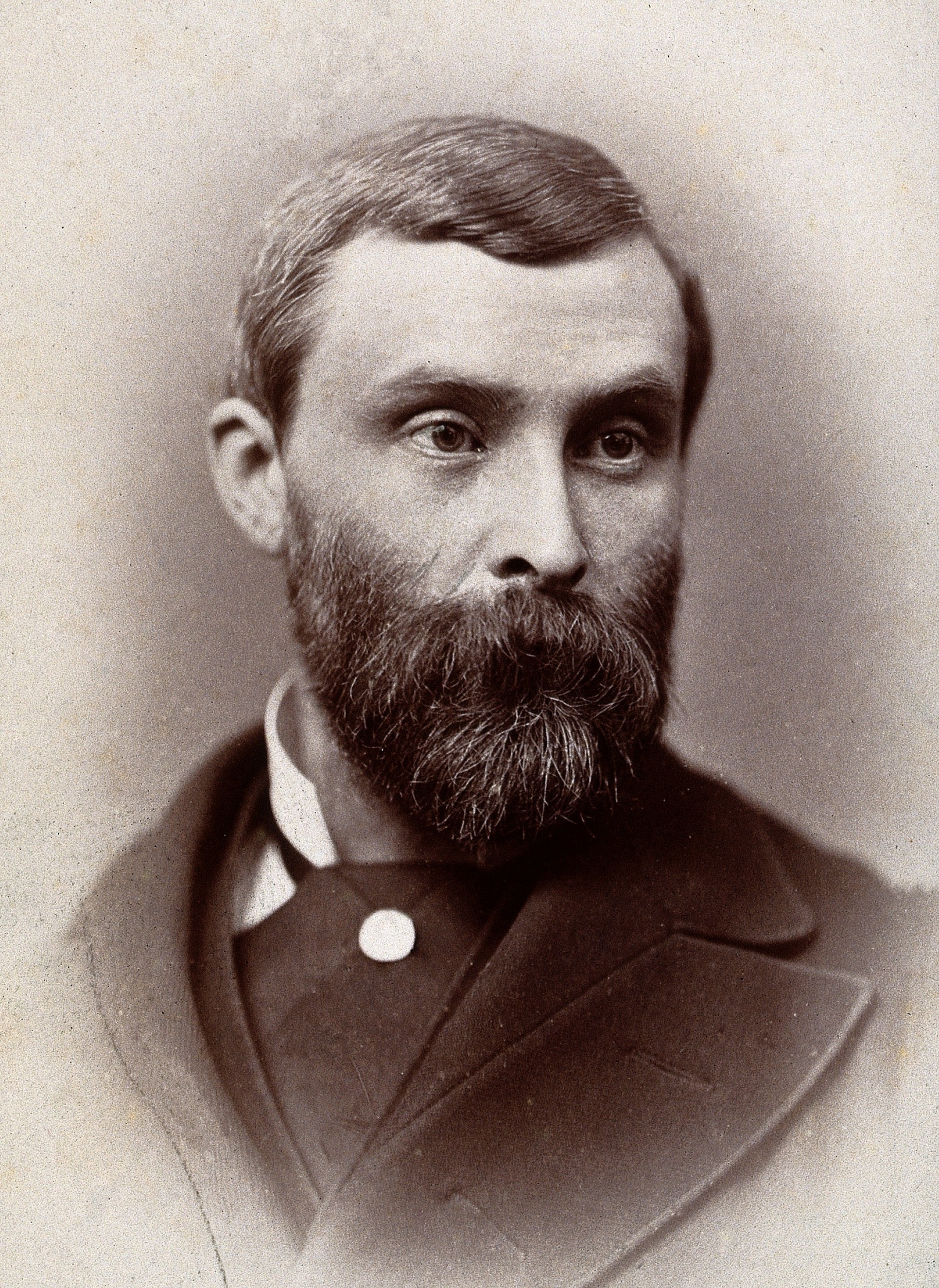

Hester Pengelly taken from the ‘Memorials of Henry Forbes Julian : member of the Institution of Mining and Metallurgy …’ by Julian, Hester Pengelly © Public Domain Available at: <https://archive.org/details/memorialsofhenry00juliiala/page/46/mode/2up>

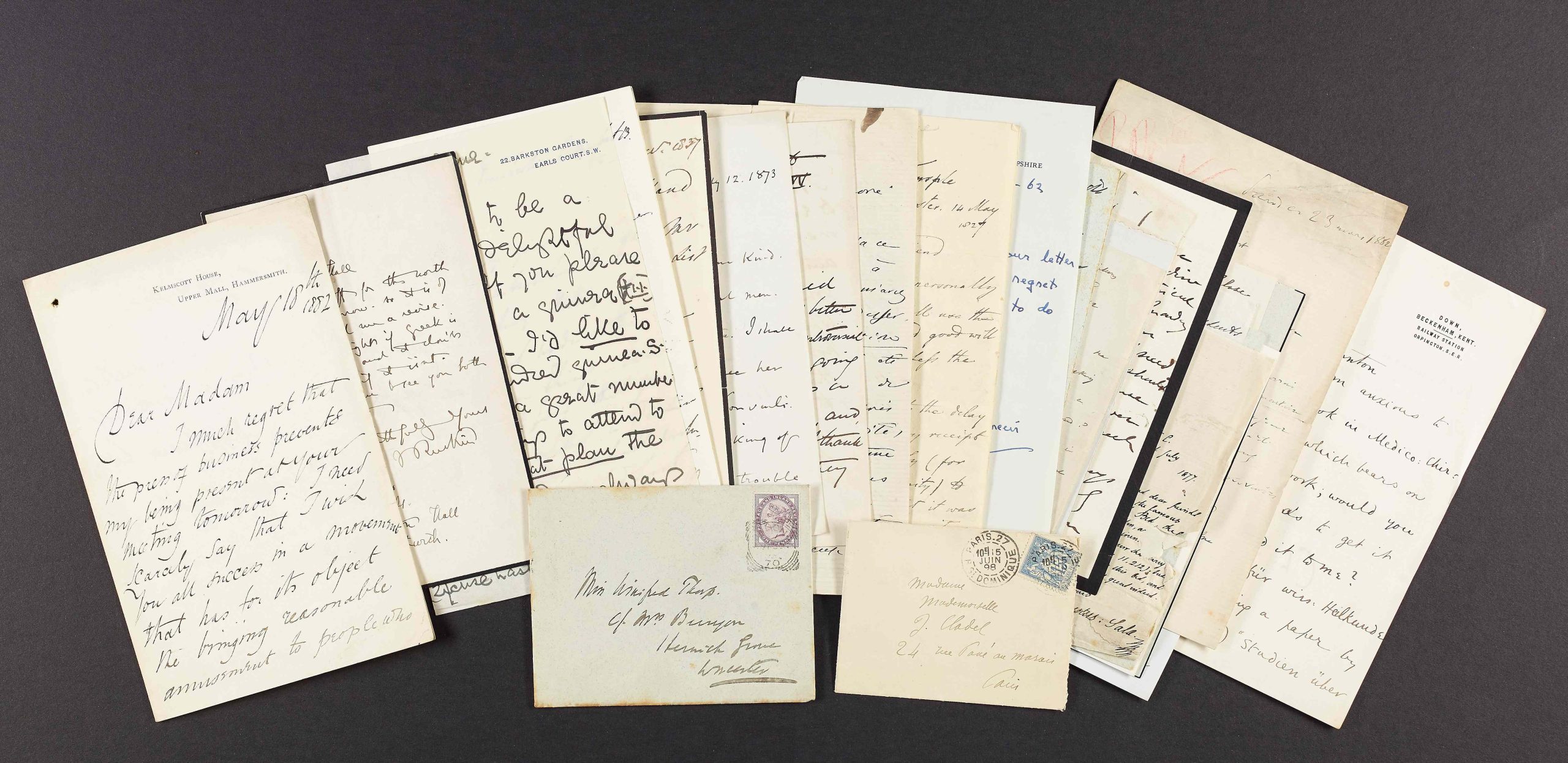

The letter was found amongst letters, papers and photographs relating to the Spriggs, Binyon and Knight Family c.1800-1940 and includes autographs which are reflective of a similar find made of directly related Pengelly family by a Work Experience student at Torquay Museum. Pengelly’s daughter Hester inherited a significant autograph collection of the rich and famous. Following her father William Pengelly’s scientific connections and due to Hester’s connection with metallurgist Henry Forbes Julian further items were added and the Hester Forbes-Julian Letter Collection includes letters from Austen to Bronte, Napoleon to Shackleton.

Before we investigate it’s important to illustrate that Charles Darwin is no stranger to Worcestershire and nearby county of Shropshire (his grandfather Erasmus had lived at The Mount where Charles was also born). Previously we have used our Palfrey collection and Darwin Correspondence Project to discuss Darwin’s relationship with Dr Gully and the Malvern Water Cure to improve his health, Darwin’s visits to Malvern with his family and later with Annie Darwin alongside his scientific work leading to the publication of On the Origin of Species.

The Darwin letter

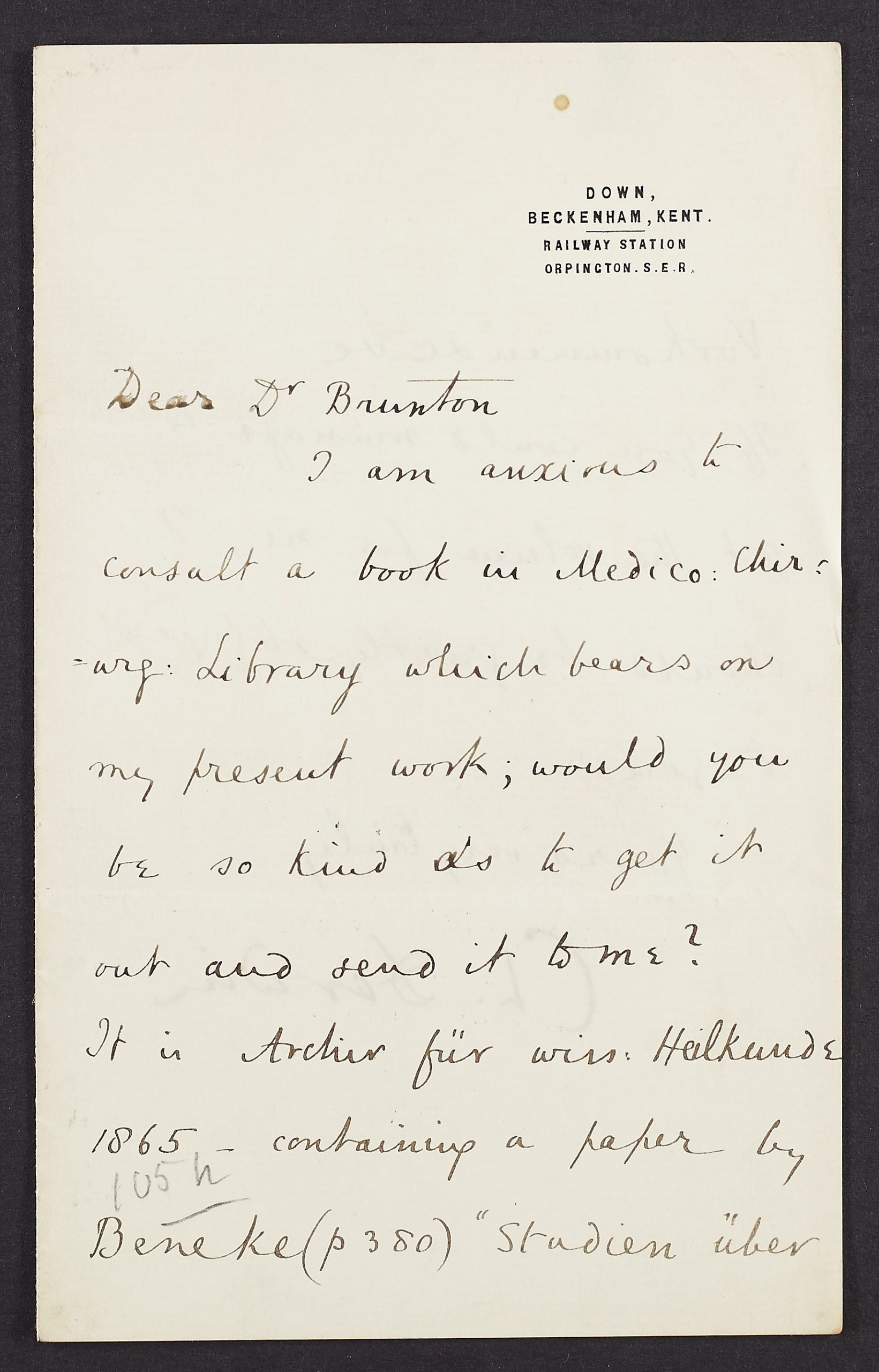

First page of Darwin letter addressed to Dr. Brunton in the Colman Collection at Finding No: BA16365/3 © Unknown

The letter, undated, is written from ‘Down, Beckenham, Kent, Railway Station, Orpington, S.E.R.’ to a ‘Dr Brunton’ and as reported in the footnotes of DCP Letter no. 9625 dated 10 Aug 1876, ‘Orpington was the nearest railway station to CD’s home at Down’ which is known as Down House. Down House is where Darwin spent much of his life with his family, following his HMS Beagle voyage from September 1842 until his death. Whilst at Down, Darwin took advantage of the increasingly sophisticated postal system at the time to correspond with scientists, naturalists, friends and family, writing thousands of letters (Stott, 2003). Darwin undertook experiments creating a ‘living laboratory’ at Down where he could test his theories, such as the study of Earthworms. The letter, as we shall see, relates to experiments Darwin was undertaking at Down at the time of writing and you can learn more his home by visiting Darwin at Home.

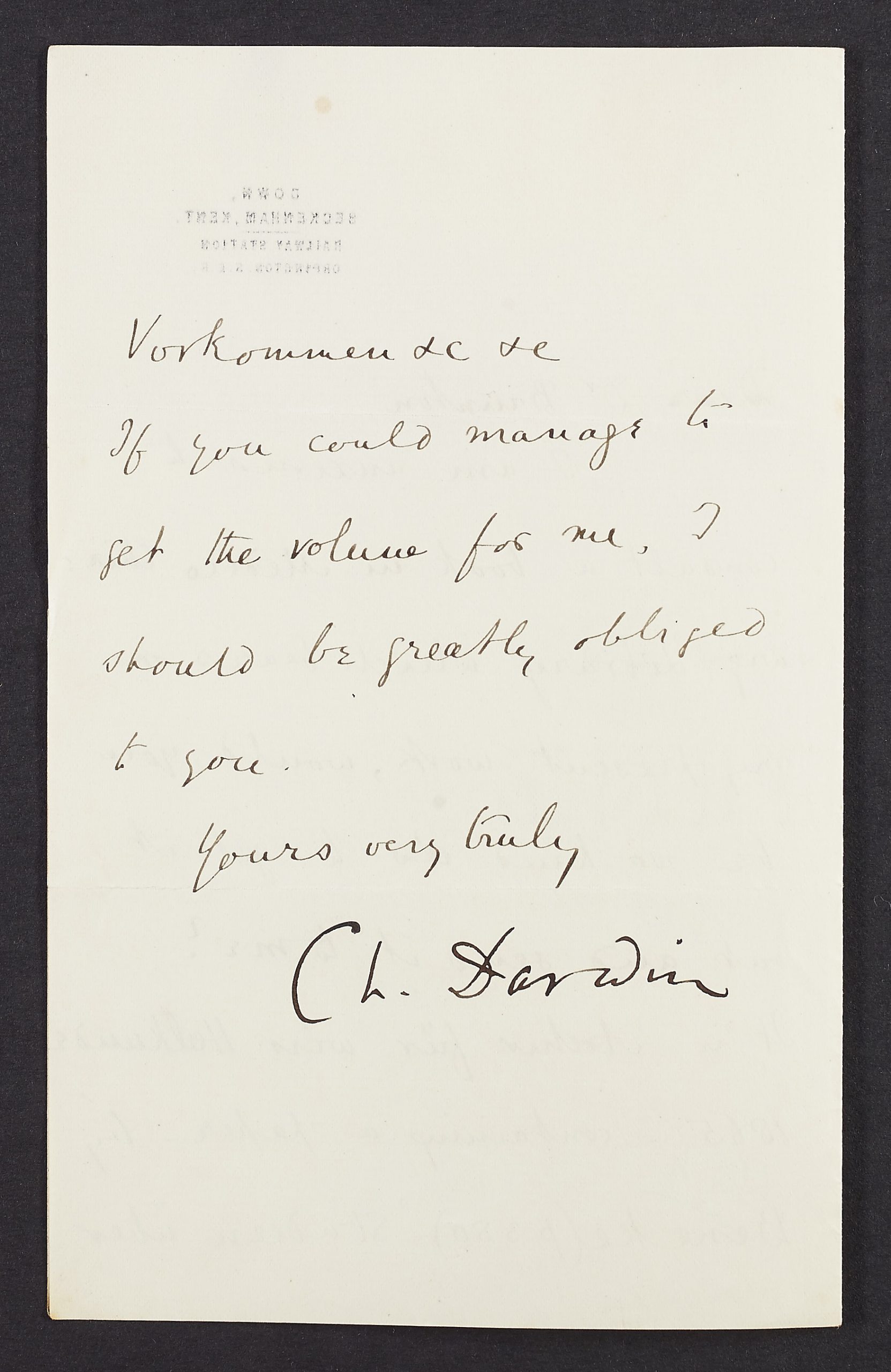

Second page of Darwin letter addressed to Dr. Brunton in the Colman Collection at Finding No: BA16365/3 © Unknown

When was Darwin writing?

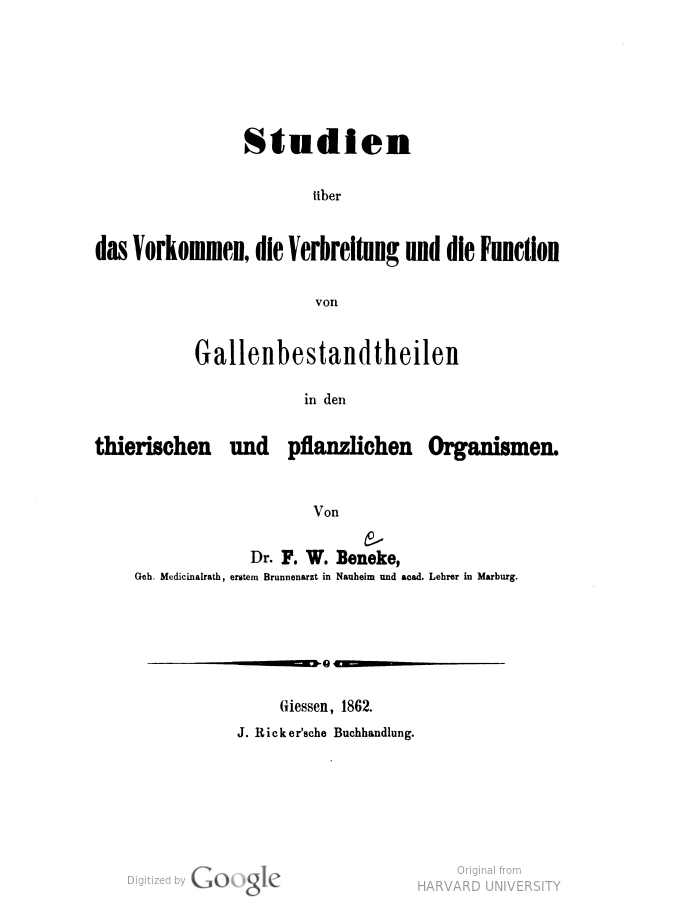

Darwin writes that he is ‘anxious to consult a book in the Medico-Chir:=wig Library’ and this abbreviation refers to a now archaic term ‘Medico-Chirurgical’ as the study of combined fields of medicine and surgery. In the letter he asks Dr. Brunton for a copy of “Studien über Vorkommen & c & c” in the ‘Archiv für wiss: Heilkunde 1865 by Beneke’. The full title of the journal article is Studien über d. Vorkommen, d. Verbreitung u. d. Function v. Gallenbestandtheilen in d. thier. u. pflanzl. Organismen. by Beneke, F.W. (1865) which is translated as ‘Studies on the occurrence, distribution, and function of bile components in animal and plant organisms’ in the ‘Archive for scientific medicine’. A version with the same title dated 1862, is available online thanks to the HathiTrust. Therefore, based on the journal date, we can be fairly certain the letter is at least written after 1865.

Title page of Studien über d. Vorkommen d. Verbreitung u. d. Function v. Gallenbestandtheilen in d. thier. u. pflanzl. Organismen by Beneke, F.W. 1862 © Public Domain Available at: <https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hc2ccz&seq=7>

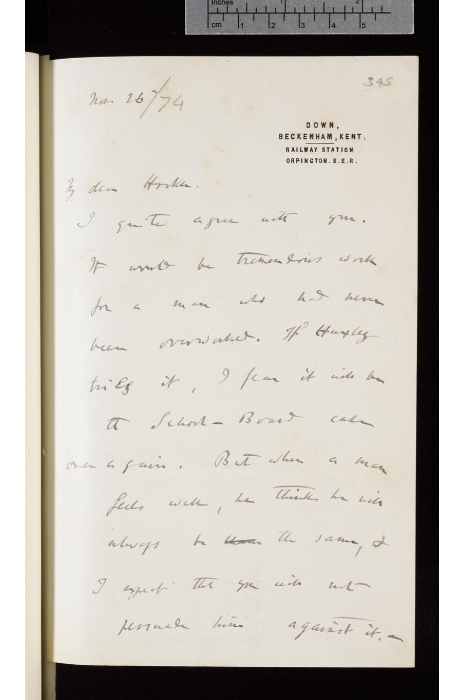

Using the Darwin Correspondence Project’s search tool, we can try and pinpoint a rough timeline based on the form of the letter, the Addressee and what Darwin is writing about after 1865. A simple search of Orpington* can be undertaken, referencing all letters which includes Orpington which illustrates he frequently sent correspondence from there. However, it is important to note that from a search of all the letters, the same headed paper Darwin uses (based on originals held on the DCP) only seem to appear after 1874.

Darwin Correspondence Project Letter no. 9734 accessed on 14 August 2025 courtesy of Cambridge University Digital Library. Available at: <https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-9734.xml>

This is in fact corroborated in the footnotes in the first few letters listed for 1874 with the statement ‘The date is established by the headed notepaper, which is of a sort that CD used from November 1874 onwards’. You can see the notepaper matches with original letter no. 9734 from Charles Darwin to his friend and Assistant Director of Kew Gardens, Joseph Dalton Hooker.

Who is Dr. Brunton?

Sir Thomas Lauder Brunton Bt. FRS 1844-1916 1881 G. Jerrard © CC BY 4.0 Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lauder_Brunton#/media/File:Lauder_Brunton_1881.jpg>

Whilst a search of Orpington Brunton in the DCP isn’t particularly useful highlighting a single letter to a Dr. Brunton. A general search for ‘Brunton, Dr.’ reveals that Dr. Brunton plays a significant role in Darwin’s scientific work corresponding between the period 1873-1882. The DCP’s summary of Dr. Thomas Lauder [T.L.] Brunton, 1st Baronet states he was a ‘physician and pharmacologist’ and ‘MD’ (Doctor of Medicine) in Edinburgh and later studied ‘pharmacology and physiological chemistry’ in Europe. It also states ‘Dr. Brunton studied the physiology of digestion and experimented on insectivorous plants for CD’ and received a knighthood in 1908.

This is useful as Dr. Brunton would have likely had access to a medical library to send the journal article to Darwin, perhaps as part of the Medico-Chirurgical Society of Edinburgh. The Society’s archives, including letters from [Sir] Thomas Lauder Brunton are shown in the University of Edinburgh Archive and Manuscript Collections. We know the letter held with us must have been written after November 1874 and ‘Letter no. 9453’ dated 11th May 1874 from Darwin to Brunton does discuss the digestion of Drosera (better known as sundews). Sundews as we shall see, have pretty disturbing ways of obtaining nutrients for growth!

Darwin and Brunton on Digestion

As shown from ‘Letter no. 9167’ as early as December, 1873, Darwin had been undertaking experiments looking at the digestion of chondrin & chlorophyll by Dionea better known as the famous Venus flytrap and later, sundew. Both sundew and Venus flytrap are part of the Droseraceae family – carnivorous plants that fascinated Darwin. Brunton had responded to ‘Letter no. 9155’ who had asked John Scott Burdon Sanderson to ask Brunton for information about the digestion of chlorophyll by animals, and also about gelatine and chondrin. Chondrin is a protein–carbohydrate substance similar to, and a constituent of commercial gelatine.

The sticky glandular tentacles of Drosera rotundifolia, photographed in Dorset, 2015 © Anthony Roach

Secretions of Sundews

Following Darwin’s publication of On the Origin of Species he was trying to demonstrate that some plants, in particular the Droseraceae had evolved incredible strategies to fix nutrients for growth. In the case of the sundew and Venus flytrap fixing nitrogen in nitrogen-poor environments by trapping and digesting insects. Sundew are characterised by glandular tentacles, topped with sticky secretions that cover their leaves. The trapping and digestion mechanism employs stalked glands that secrete sweet mucilage to attract and ensnare insects and enzymes to digest them and glands to absorb the resulting nutrient soup.

The famous Venus flytrap Dionaea muscipula, a plant native to the East Coast of America photographed in Darwin’s Greenhouse, Down House, Kent © Anthony Roach

In ‘Letter no. 9453’ to Dr. Brunton, Darwin refers to an experiment where he attempted to ascertain whether casein or albumen in milk excited the digestive secretions of Drosera, most likely Drosera rotundifolia (common sundew). He enclosed, for examination by Brunton, residue from skimmed milk which had been on the glands of Drosera asking Brunton to confirm his views.

Insectivorous Plants

On page 114, in Darwin’s Insectivorous Plants he describes this experiment and Dr. Brunton’s examination of the slides ‘As I was not familiar with the microscopical appearance of milk, I asked Dr. Lauder Brunton to examine the slides, and he tested the globules with ether, and found that they were dissolved. We may, therefore, conclude that the secretion quickly dissolves casein, in the state in which it exists in milk.’

Sundews and other insectivorous plants in the foreground in Darwin’s greenhouse at Down House, Kent © Anthony Roach

Subsequently as Steve Jones explains in Darwin’s Island Darwin observed

‘the sundew, he found, had feeble roots – evidence that most of its nutrition came from its grisly way of life. He brought some specimens back to his greenhouse and began to explore how they did their job.’ (Jones, 2009, p.53)

Through observation and direct experiments, Darwin observed that plants secrete enzymes to protect their seeds and leaves against attack and in sundews used, all-but-the-same enzyme, for a much sinister purpose – to trap and digest insects (Jones, 2009, p.71). Jones goes on to say:

‘It was a first step in a decade of work that produced a powerful justification of his claim in The Origin that natural selection, could, starting from a separate places, end up, with much the same result.’ (Jones, 2009, p.53)

Therefore, whilst we cannot be certain of the exact date of the Darwin letter, its’ contents and the correspondence that exists suggests that Charles Darwin was chiefly concerned with digestion in plants and animals during the late 1870’s. The letters after 1875 to and from Dr. Brunton relate to matters from legal expenses, Brunton thanking Darwin for a copy of Erasmus Darwin and Darwin giving a copy of his Earthworm book, following Brunton’s collected writings.

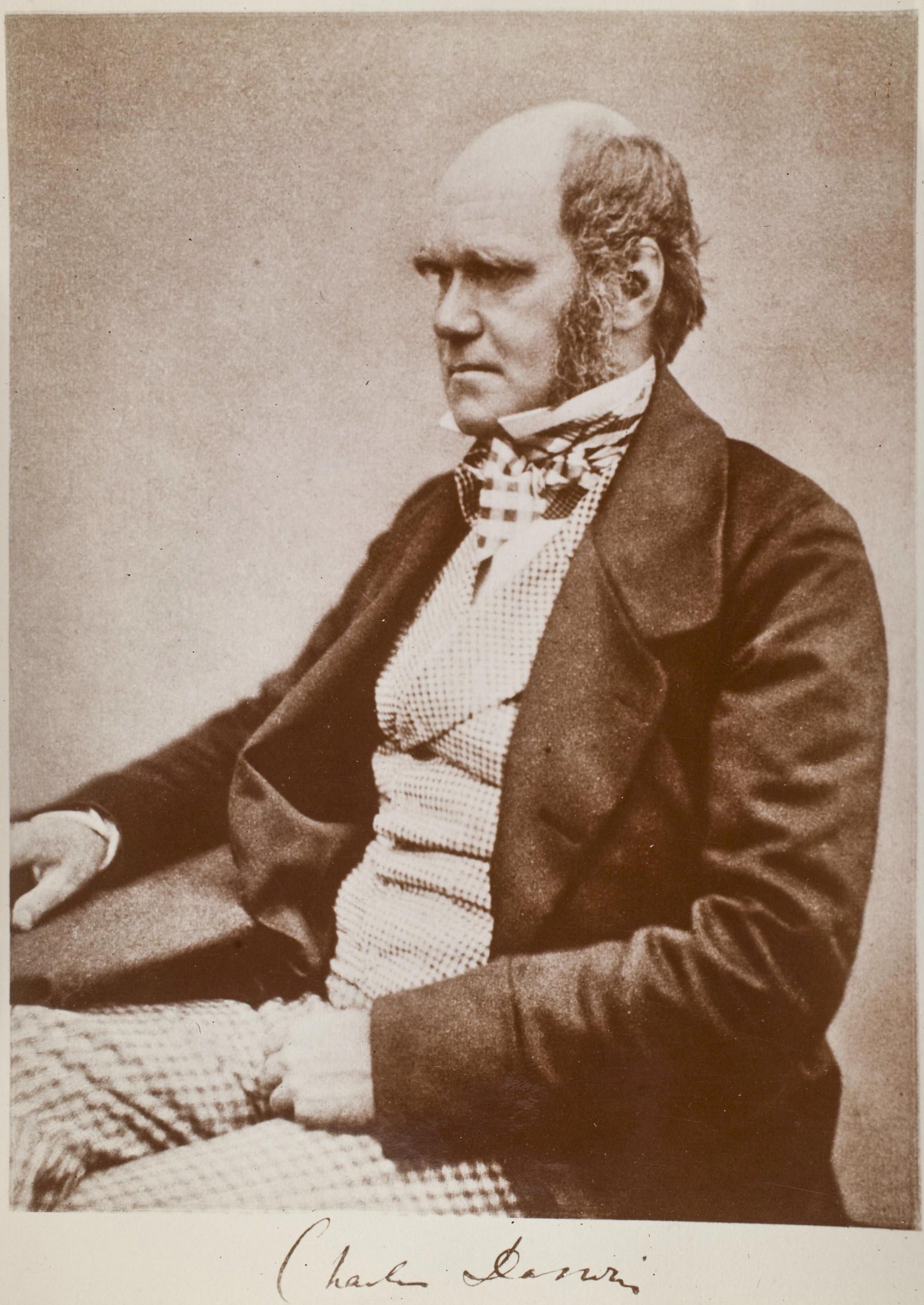

Photograph of Charles Darwin by Maull & Fox c.1854 published in Karl Pearson, The Life, Letters, and Labours of Francis Galton (1914) © Public Domain Available at: <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Charles_Darwin_seated.jpg> © Public Domain

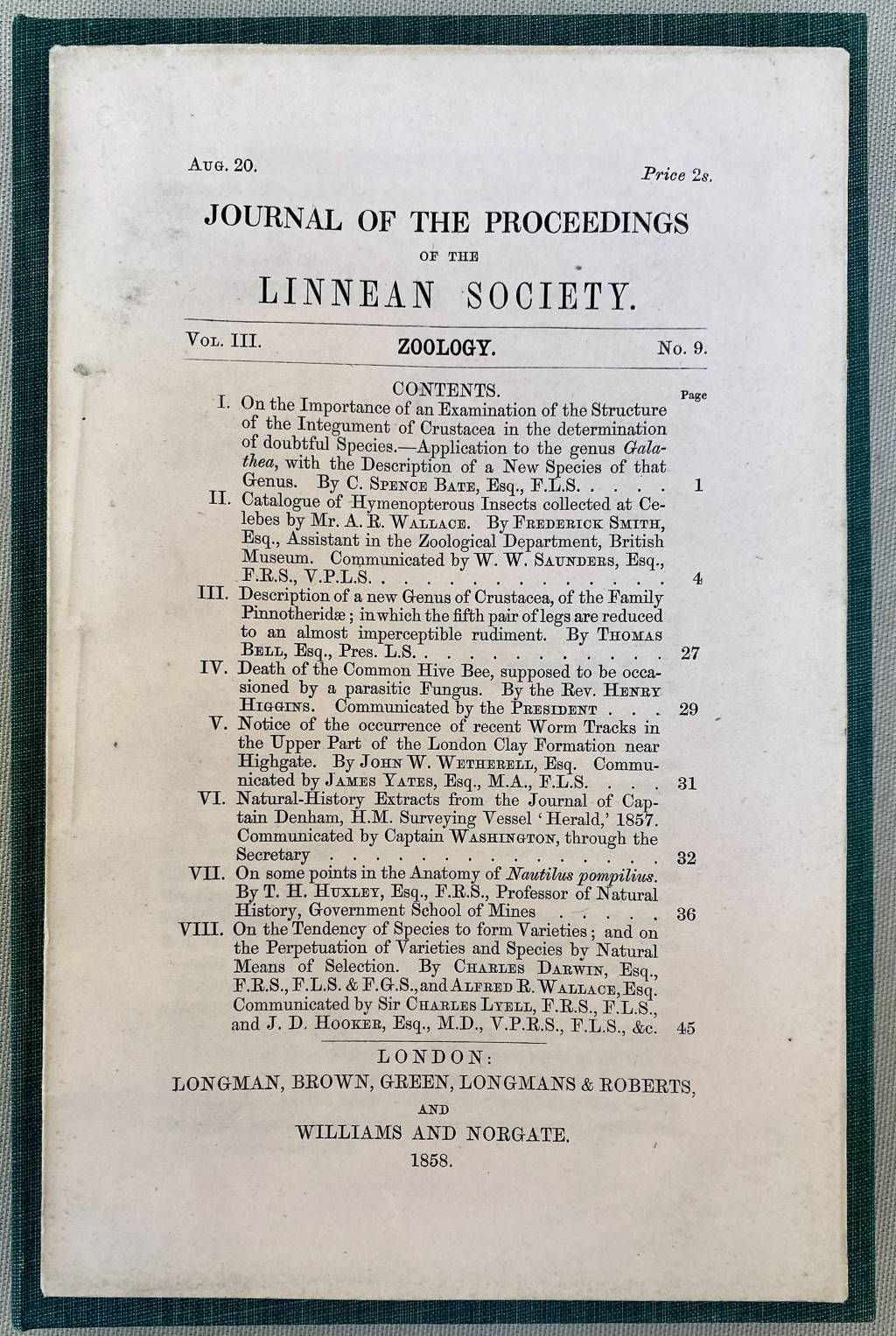

Darwin’s great insight with Insectivorous Plants is that he sought to demonstrate that plants from widely separate parts of the world had evolved similar strategies to survival in challenging, nutrient-poor environments. This was further evidence which strengthened his theory of evolution by natural selection, which he jointly published with Alfred Russel Wallace (who came to the same conclusions based on his own observations and distilled in him whilst confined with fever in his hut, on Ternate, now Indonesia). A reading of the two papers occurred at a meeting of The Linnean Society on 1st July 1858, and published on the 20th August, with little, if any impact on its audience at all. Wallace’s annotated copy of the paper is shown here.

Image: Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society dated 20 August which lists Darwin and Wallace’s joint publication of the Theory of Evolution of Natural Selection as “On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection…” © Public Domain

Scientists are continuing to make discoveries concerning their evolutionary lineages today. In the UK alone, there are three distinct species of sundew, so if you want to observe a truly amazing plant in action, why not visit a moorland or bog near you! We hope to share more about the Colman collection of letters, once the collection has been fully catalogued.

Key Sources used:

The Darwin Correspondence Project

Darwin and The Barnacle

Author: Stott, Rebecca. 2003 – Available at Malvern Library, Local Reference

Darwin’s island : the Galapagos in the Garden of England

Author: Jones, Steve 2009. – Available at Level 3: Main Collection – 576.82 JON

Please note all efforts have been taken to identify copyright owners, we apologise for any inadvertent infringement and invite the copyright owners to make contact where necessary.

Post a Comment