Royals and Rebels – Finding the Battlefield

- 6th October 2025

This is the first of three posts highlighting the discoveries made during archaeological investigations undertaken by Worcestershire Archaeology on part of the site of the Battle of Worcester. Over the mini-series we explore how the 17th century battlefield surface was located, the artefacts found there, and what this can tell us about the Battle.

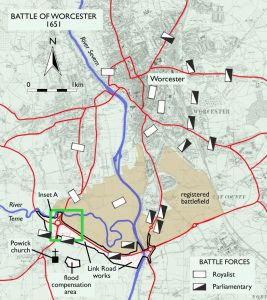

Documentary evidence suggests the Battle of Worcester began in the early afternoon of 3rd September 1651 on a floodplain to the south of the city, near to where the Rivers Severn and Teme merge. Fighting was focused around nearby Powick Bridge – a key strategic point – which the Parliamentarians needed to cross to enter Worcester itself. Having destroyed the two northernmost piers of the bridge in readiness for the Parliamentary attack, Royalist forces were positioned in the surrounding fields to defend the bridge and the city beyond.

Map highlighting where fieldwork took place

In 2017-22, Worcestershire Archaeology had a unique and exciting opportunity to examine this part of the battlefield when 1.9km of the A4440 Worcester Southern Link Road was converted from single to dual track. The original road was built in 1985 and no archaeological investigation took place then. In the intervening years, the line of the road has also come to define the southern border of the Historic England-registered battlefield, somewhat strangely, as the arena is known to have extended across fields further south.

As you would expect of an area that is prone to flooding, the actual ground on which the soldiers fought is no longer the surface we see today, but lies beneath layers of more recent river alluvium (the clay, silt, and sand deposits left by flowing floodwater in areas next to rivers). Geophysical survey is commonly used to gain an idea of what might lie below the ground, such as ditches, pits and walls. However, it was unlikely to help us here as a scatter of artefacts is probably all that remains, so how could we find the battlefield? We needed to take an innovative and somewhat experimental approach, one which was made possible due to the location of the site on a flood plain.

Archaeological investigations in progress for Worcester’s Southern Link Road scheme.

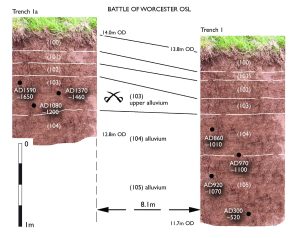

Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) is a well-established technique used to date sediments by determining when certain minerals within them were last exposed to light. We knew it had been used successfully for deeper alluvium deposits elsewhere within the Severn valley, but the technique had been little used for such recent periods. Quite how effective it would be for this project was therefore unknown, but by taking a number of OSL samples from different depths we hoped to find the buried 17th century horizon.

Sample being taken for optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating by the University of Gloucestershire

The first OSL results (Trench 1) suggested that it would be possible to establish a dating sequence for the floodplain alluvium. This was very encouraging, so a second batch of samples were collected by Professor Phillip Toms, professor in physical geography at the University of Gloucestershire, which extended into the very uppermost part of the alluvium (Trench 1a). The highest sample returned a date of AD1590–1650. Putting all the data together revealed a consistent depositional sequence that suggested the top few centimetres of the upper alluvium had likely formed during the mid-17th century.

Alluvial layers marked with OSL sample dates, showing how the battlefield level was identified (created by British Archaeology magazine with information from Worcestershire Archaeology)

As work progressed however, it soon became clear that this information should not be applied too broadly. Better preservation was identified where traditional water meadows (used to cultivate hay and protect from ice and frost) had continued in use beyond the 17th century. Fortunately, this better preservation applied to much of the land closest to the route of the road widening. With this new knowledge in place, we could now begin to target areas for artefact recovery.

Would the battlefield give up its secrets? Find out in the next blog in the series – Royals and Rebels- The Artefacts

This blog is based on an article by Derek Hurst and Richard Bradley, first published in the January/ February 2023 issue of British Archaeology magazine and Bradley, R. and Hurst, D. (2023). Worcester Southern Link Road (Phase 4): Archaeological investigations 2018–2023. Worcestershire Archaeology unpublished report.

The project was undertaken by Worcestershire Archaeology for TACP (UK) Ltd, working on behalf of Alun Griffiths and Worcestershire County Council. The University of Gloucestershire carried out the OSL dating. Photos and figures are copyright of Worcestershire Archaeology, unless otherwise stated.

Post a Comment