Ideas That Changed the World

- 17th October 2018

The turn of the nineteenth century was an important point in our recognition and understanding of the Ice Age. The whole of the earth’s history had been understood to fit within the few thousand years described in the bible, but this was about to change.

Eighteenth century scientists wrestled with problematic discoveries of elephant-like bones found far from the tropical areas they usually live in. It was thought they’d been washed into Britain by a great flood thousands of years before. A discovery in Siberia would change everything. A hunting party discovered the frozen body of a mammoth that had died thousands of years before. It was brought back for display in St Petersburg and, importantly, it proved that the mammoth was a different species to the elephant and had lived in a much colder climate.

Mammoths in Worcestershire – reconstruction drawing by WAAS illustrator

Antiquarians began considering the use and age of stone objects we now know were tools. At the end of the 18th century John Frere of Norfolk wrote that these stones, found 12 feet below the ground alongside the bones of strange animals, must belong to a very remote time ago indeed.

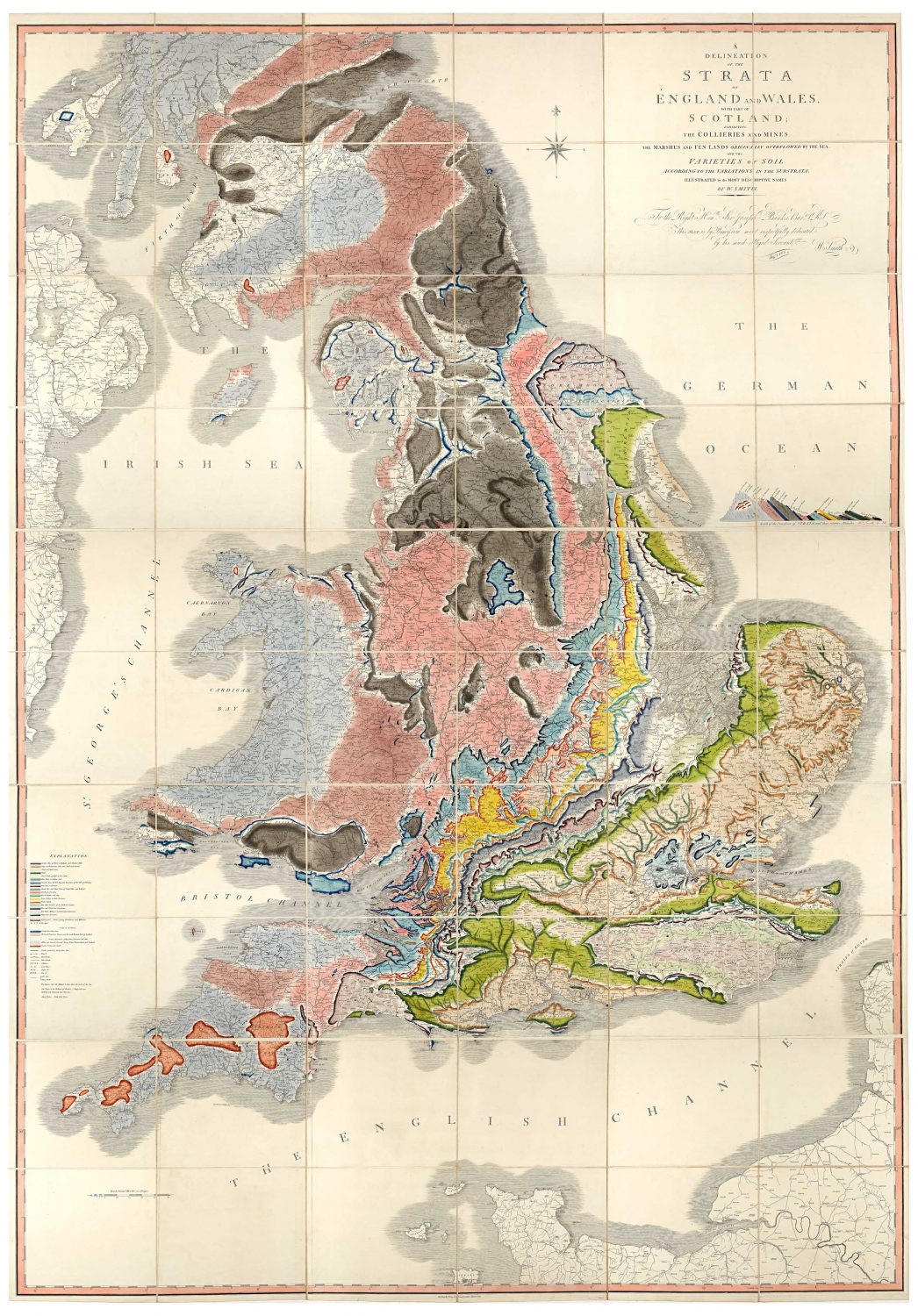

A few years later, an engineer called William Smith began mapping the layers of rock he found in Britain and the fossils found within them. Smith and geologists like him realised that each layer of rock belonged to a different time and provided a record of the plants and animals that lived within that time.

William Smith’s 1815 Geological Map of England, Wales and part of Scotland

Ideas about the world were changing: the earth was ancient, much more ancient than the few thousand years previously thought. The climate had been far colder and large extinct animals had lived alongside humans who had made strange stone tools that had survived for millennia.

It took the persistent dedication though of a French customers inspector, Jacques Boucher de Perthes, for the antiquity of humanity to finally be accepted within academic circles. Working in gravel quarries along the Somme river, Boucher de Perthes began collecting stone tools from geological layers containing extinct animal remains. His 1841 publication was not well received, but a few were prepared to contemplate his discoveries and travelled to see the gravel pits first-hand.

In 1859, a flint handaxe embedded in an ancient gravel deposit was also observed and recorded by two English academics. Before the month was out, the Royal Society in London had been informed and views began to change: research slowly turned from proving the concept of a ‘prehistory’ to discovering more about it.

Post a Comment