Monthly Mystery: the Infirmary Bones

- 1st March 2016

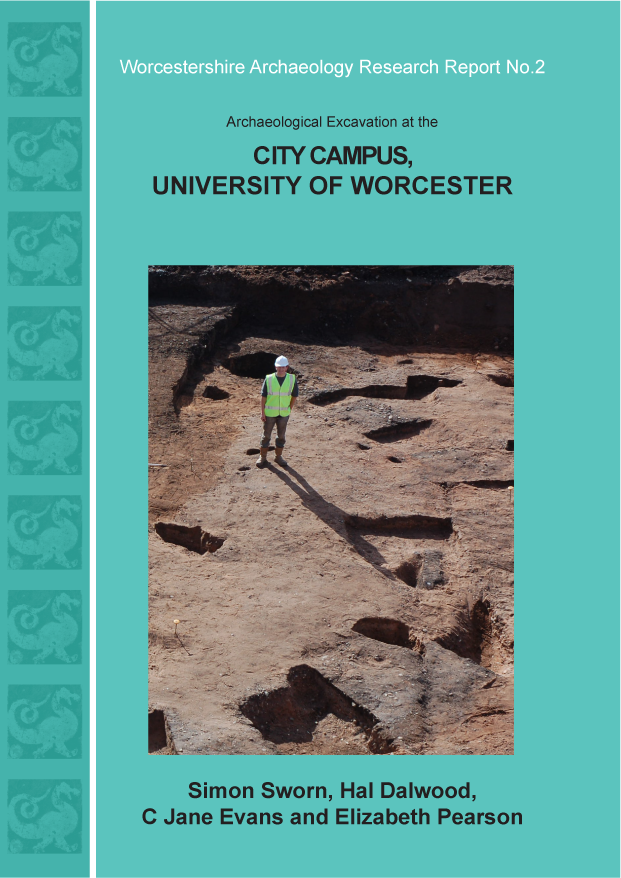

During building work at Worcester’s Royal Infirmary between 2007 and 2010, as it was undergoing the transformation from former hospital to the University of Worcester’s City Campus, our archaeologists were brought in to investigate the history of the site.

An excavation was carried out in the southern part of the grounds of the Infirmary, which revealed the remains of several Roman buildings, quarry pits and rubbish dumps. The area was agricultural land in the Roman period, with evidence for buildings including a crop-processing barn.

Excavating Roman remains to the south of the Infirmary building ©WAAS

Excavating Roman remains to the south of the Infirmary building ©WAAS

The rubbish dumps contained lots of domestic rubbish, including pottery, animal bone, textile equipment, jewellery and glass, a fascinating insight into the lives of the occupants of Roman Worcester. The report on the excavations is available here.

But the old Infirmary complex had a few more recent secrets to give up, too…

In 2009 work was in full swing on the north half of the site, around the Infirmary itself. Although the building of the original Infirmary, which opened in 1771, probably disturbed a lot of the earlier archaeology, there was a chance that some might remain, so our archaeologists were on hand to keep an eye on the building works.

As the construction workers began to dig trenches for drainage pipes and services, they discovered some bones. When archaeologists Tim and Tegan Cornah began to carefully expose them it soon became clear that there was something very peculiar about them…

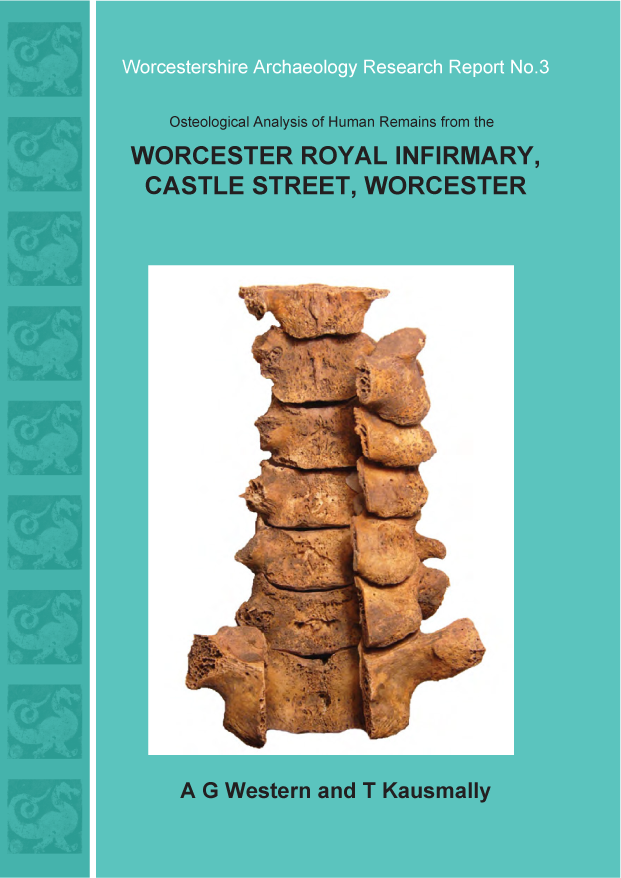

Three pits containing human bone were discovered, along with another group in ground probably disturbed by 20th century construction activity. None were individual burials, and they had some strange features: some had evidently been neatly sawn through, others had visible cutmarks; metal fixings and copper/iron staining were visible on others. In total, 1828 pieces of human bone were recovered. Associated artefacts such as pottery and medical instruments (illustrated below) tell us that the remains were probably buried sometime between the late 18th and mid-19th centuries.

Medical instruments discovered with the bones. L: stricture dilators for unblocking of the urethra. R: ‘Simpson type’ bladder or uterine sound (probe)

Medical instruments discovered with the bones. L: stricture dilators for unblocking of the urethra. R: ‘Simpson type’ bladder or uterine sound (probe)

The remains themselves were analysed by osteoarchaeologists Gaynor Western and Tania Kausmally of Ossafreelance. Their fantastic report is available here (contains images of human remains). The remains include surgical waste from amputations as well as many examples showing signs of dissection and use in anatomical studies, providing a unique insight into medical treatment and Worcester’s role as an important centre for surgical teaching during the early years of the Infirmary.

However, there’s a bit of a mystery attached to them. Why were they buried in the grounds of the hospital? The Infirmary had no designated burial ground, unlike many other contemporary hospitals of its type. The history and ethics of obtaining human bodies for anatomical study is mired in tensions.

On the one hand the drive for scientific understanding, professionalization and empirical experimentation in medicine, of enormous benefit to the living, required a steady stream of study material. Worcester was at the forefront of medical innovation in the early 19th century: local man Charles Hastings founded the forerunner of the British Medical Association at the Infirmary in 1832. In the same year, the Anatomy Act expanded the legal sources of remains for study to include unclaimed bodies of paupers from prisons and local workhouses.

Charles Hastings, founder of the BMA, photographed in 1864

Charles Hastings, founder of the BMA, photographed in 1864

On the other hand, public attitudes towards medical use of newly-deceased corpses were frequently at odds with those of the medical profession. Prior to the Anatomy Act, the only legal source of bodies was the corpses of executed murderers. For some time, however, demand had outstripped supply, leading to a thriving trade in illegal grave-robbing which sparked public revulsion. The complicity of the medical profession in this practice did not go unmarked: a riot in Aberdeen caused by the dumping of human remains in the yard of an anatomy school was just one of many. For its part, the profession campaigned long and hard for the Act, whilst sympathising with those caught going to desperate lengths to obtain specimens: in 1827, the Worcester Medical and Surgical Society, moved by the plight of a fined colleague, voted:

“a sum of 10 guineas to this surgeon in testimony of the deep feelings of sorrow… that so severe a sentence should have been inflicted upon him for having exhumed a body for the purpose of teaching the anatomical art” .

Ossafreelance’s report considers the legality of the remains discovered at the Infirmary. Some of the amputated elements are clearly hospital waste, and others (especially the parts exhibiting signs of metal fixings) were probably from skeletons wired up as teaching models: the 1832 Anatomy Act didn’t specify how existing remains held by hospitals should be treated. However, the analysis indicates that others show clear signs of having been dissected in the course of anatomical investigations, and the Act did specify that following investigations, bodies should be given a Christian burial.

Do any of the body parts discovered post-date the Act? Well, there is one smoking gun that gives us a hint that at least some of the waste from amputations was acquired after 1832: a small fragment of the distal (bottom) portion of a femur (thigh bone) is characteristic of a revolutionary new transcondylar ‘single-flap’ amputation technique developed by Worcester surgeon Henry Carden, and first adopted at the Infirmary in 1846 (an illustration and discussion of Carden’s technique can be found in this paper).

The remains from Worcester are the largest such assemblage ever discovered in association with a provincial hospital of this date. The individuals represented exhibit high levels of inflammation, infection and trauma; they evidently led tough lives, many cut short by gallows, prison or workhouse. These were men, women and children on the margins of society: the poor, the disenfranchised, and the criminal. Scattered, fragmented and unceremoniously deposited in shallow pits, their treatment in death sadly mirrored their status in life.

The discovery raises difficult questions about the balance between the advancement of medical science and ethical and moral considerations regarding the treatment of the human body, at a time in which, not unlike today, the rapid pace of scientific progress left governments and regulators struggling to keep up. Charles Hastings was a tireless campaigner for the rights of the poor and for rigorous medical ethics: he would doubtless have strongly contested the popular view among the public that dispersal and disposal of body parts was a transgressive act. Indeed, he arguably did more than any other to improve the lives of the poor in Worcester, investing his own money in improving workers’ housing in order to combat the scourge of cholera.

A little bit of mystery remains. Who buried them? Was it a clandestine act, concealing illegal activity? Or simply a routine disposal of material that had served its scientific or educational purpose?

We’ll probably never know who they were, or how they came to be under the surgeons’ or students’ knives. But there’s some consolation in the knowledge that they played their role in the advancement of medical science for the benefit of those to come, and that the accident of their discovery has opened an extraordinary window into the lives and deaths of the poor in 18th and 19th century Worcester.

Rob Hedge.

The project was funded by the University of Worcester, and managed by Cathy Patrick of CgMs Consulting. James Dinn, Worcester City Council’s Archaeological Officer, was instrumental in making this work a condition of planning permission. The archaeological site work was carried out by Tim and Tegan Cornah of Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service’s Archaeological Field Section, and the analysis of human remains conducted by Ossafreelance.

For more information on the people, hospital and techniques mentioned, do visit the wonderful Infirmary Museum on the University’s City Campus, and its sister museum, the George Marshall Medical Museum on the site of the Worcestershire Royal Hospital.

For more information on the historical context of the remains, see this poster by osteoarchaeologist Gaynor Western.

The reports are now available to read too

This is a fascinating insight into the period and indicates just how much there still is to learn about the past through archaeological studies.