Find of the Month – June 2018

- 3rd July 2018

What to pick this month? June began by finding a mammoth tusk, which is now on display at Worcester City Museum & Art Gallery (as it turned up just in time for our Ice Age exhibition). We also found a mysterious decorated ceramic object in Worcester, but this remains a mystery that no one’s yet solved. Something we’ve not yet featured for Find of the Month turned up too though – a Roman coin.

Mystery item found in Worcester (although our finds specialists are yet full analysis it).

Don’t you find coins and golden treasure all the time? Despite popular belief, we don’t. Imagine you lost a valuable item – would you say ‘oh well, never mind’ and move on, or search for it? Precious objects are rarely lost as stray finds, so it’s only when they’ve been intentionally buried (as an offering, grave good or hoard for safe keeping) that they tend to enter the archaeological record. The exception to all of this, of course, is small change. This Roman copper coin is small, just 14mm across, and was found at the base of storage pit on a site near Evesham along the River Avon.

Roman copper coin – two soldiers just visible on reverse (left image) with head on obverse (right image) – millimeter scale

As you can see, the coin is pretty worn and its faces are hard to make out. Based on its size and remnant design though, a local coin specialist has been able to date it to the 330s AD; as the Roman Empire began to decline. As coins frequently change with each new ruler, they’re useful dating evidence. But when coins aren’t found, or it’s an era without coinage, how do archaeologists know how old things are? How do we know Bronze Age pots are Bronze Age? How do we tell a cattle bone is Roman and not medieval?

Our coin is most likely to be the Two Soliders design above – taken from Reece & James (1986) Identifying Roman Coins.

The answer is a combination of relative and absolute dating. Relative dating uses information about where an artefact was found and what it is, to place it in a sequence of finds from oldest to most recent. Absolute dating provides a calendar date for how old something is, often via scientific analysis; most commonly radiocarbon dating or dendrochronology. It’s the combination of these two types of dating that’s most helpful – establishing a relative chronology for an archaeological site or collection of finds means that only a few absolute dates are needed to tie the otherwise floating chronology to calendar dates.

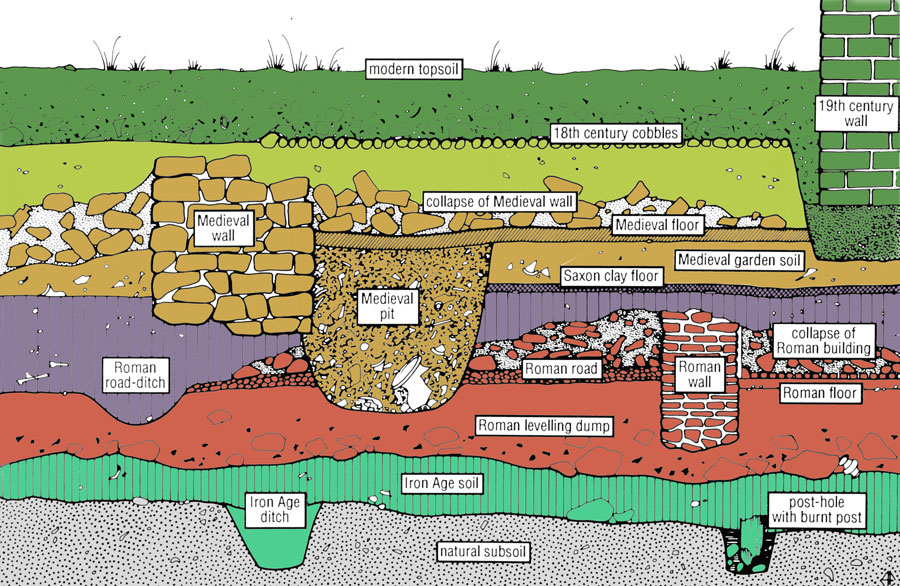

This is not always as straight forward as it sounds. Relative dating relies on stratigraphy and typology, which are not always easy to establish, and even absolute dating techniques have precision and calibration issues. Stratigraphy is the order and connection between archaeological layers, deposits and features in the ground. The diagram below illustrates this nicely, although in real life there are no labels and almost everything is (different shades of) brown; it can be very tricky to untangle what’s going on.

Stratigraphy diagram showing a section through an archaeological site (© Canterbury Archaeological Trust)

Typologies try to establish how an object changes over time, as fashions, use and techniques change. Mobile phones, for example, started off the size of bricks then shrank as technology improved and have grown again in response to our demand for larger viewing screens, supported by the development of touch screen technology. Antiquarians and early archaeologists put a great deal of effort into establishing typology for all sorts of objects, and even created meta-typologies to tie them together. This can be really useful, especially when no means of absolute dating is possible. However, it relies on us to make assumptions about how things changed in the past, meaning that typologies can be incorrect and misleading.

Until the second half of the 20th century, western Europeans often assumed that history was one linear progression from primitive societies to a high civilised future. This is not true. Whilst technological knowledge does tend to accumulate over time, there is no inherently superior or more ‘civilised’ society – societies can be more or less complex in different ways and they do not exist along a single trajectory of change and development. The same applies to objects: fashion influences style and shape as much as technology. During the Anglo-Saxon era pottery was poorly handmade in comparison the earlier Roman wheel-thrown pots. However, there was a cultural rejection of Roman ways after the empire collapsed and the Anglo-Saxons became incredible metal workers who used pottery for few purposes than the Romans.

Added to these problems is the fact that objects don’t always go in the ground when you’d expect – a coin may be kept long after its creation and even after it’s fallen out of circulation. A medieval person digging over ground containing Roman remains may also cause earlier finds to fall into their pit or ditch. So, our little Roman coin may not look too exciting, but hopefully it’s given you an insight into the complex web of evidence archaeologists have to untangle and the techniques we can use to avoid the pitfalls of our own assumptions.

This is precisely all that I had to learn when I first joined the then ,Hereford and Worcester Archaeology way back in 1982-3. which enabled me to further my interest in archaeology So my thanks to John Price, Derek Hurst and Simon Woodywiss. This post will be of great help to today’s students.