Find of the Month – August 2018

- 14th September 2018

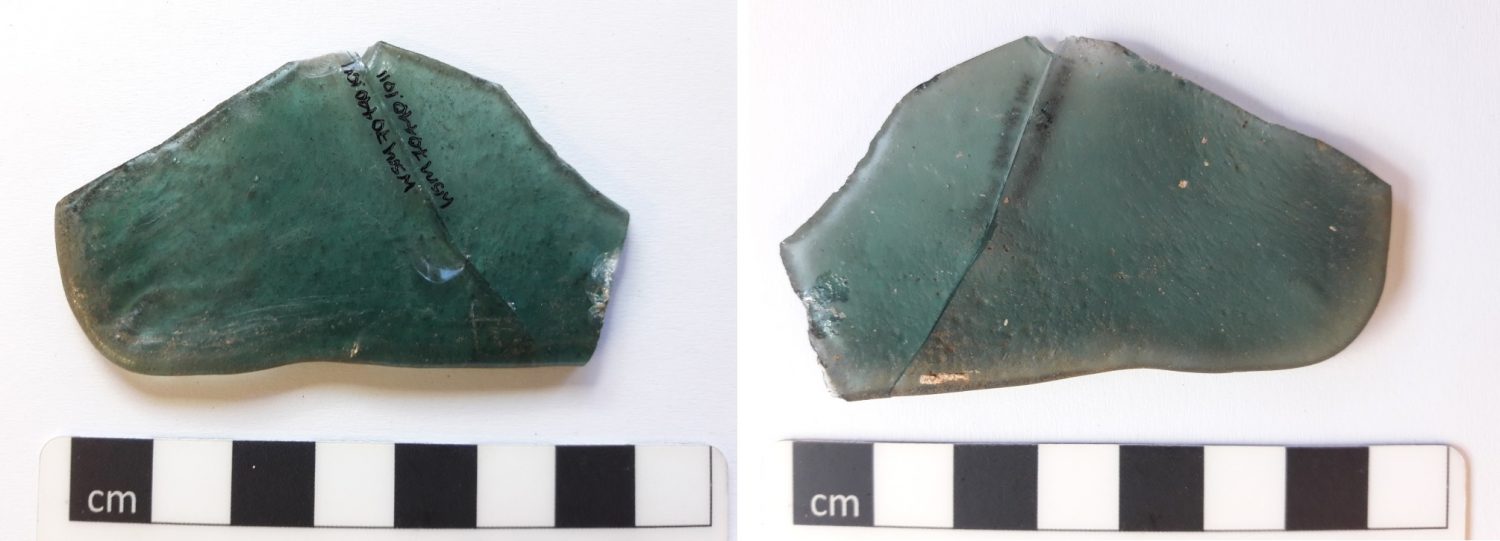

One of the many things our archaeologists found in August is this beautiful piece of bluegreen tinted glass. The tiny bubbles in the glass tell us that it’s old: Roman, to be precise.

Roman window glass found near Evesham – the tiny bubbles are characteristic of Roman glass.

Roman glass was high quality and survives impressively well in the ground – so much so that it’s hard to believe it’s almost 2000 years old. Even more incredibly, this piece of glass comes from a Roman window. Yes, glass windows first appeared in Britain during the Roman era (but only if you were extremely wealthy).

Look at the photo below and you’ll see that it’s the corner of a square window pane. One side is smooth and shiny, whilst the other is hazy. This, along with the wavy edges, tells us the window pane was created by pouring molten glass onto a flat stone or sand surface. A frame may have been used or the molten glass worked by hand to cast it into the desired shape. From the 3rd century AD onwards, window glass with two shiny surfaces was produced (by blowing a cylinder that was cut and flattened whilst hot) telling us that this fragment is older; either early or middle Roman.

Corner of window pane with one shiny surface (left) and a rough back from casting (right) – the writing is an archive label.

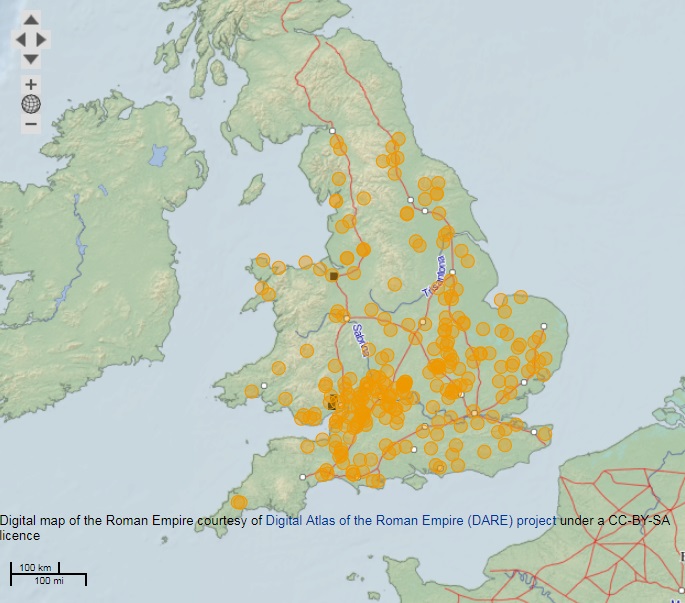

Only one other site in Worcestershire has produced Roman window glass (Bays Meadow villa in Droitwich), making this an important find. Across England, window glass is most frequently found on Roman farm and villa sites, although it is not unheard of from large townhouses and public baths. Roman windows were made to keep the weather out and warmth in; they certainly weren’t easy to look through at 3-4mm thick with one matt side. So few fragments have been found that it’s rarely possible to reconstruct the original pane size, but most windows were probably 30-40cm square. Traces of mortar on edge pieces suggest that they were sometimes set into stone surrounds, although wooden window frames were probably used as well.

Distribution map showing all the Roman sites in England and Wales where window glass has been found (courtesy of the Rural Settlements of Roman Britain project).

Glass was not produced in the Evesham area, where this window fragment was found, or anywhere else in Britain during the Roman era. Archaeological evidence suggests that glass was only produced at a few sites across in the Roman Empire and imported as large lumps that were broken up, melted and shaped. Glass beads have been worn in Britain since the Bronze Age, but it was during the Roman era that glass became more widely used, particularly for vessels and tableware. As glass had to be imported, which was presumably expensive, it was often collected up and recycled into new items. Perhaps that’s what happened to the rest of this window pane, leaving just one corner to be swept up and dumped with building rubble in an old stone water cistern.

After the Roman Empire collapsed and the army left Britain in 410 AD, glass continued to be imported and used to make beads, vessels and (after the arrival of Christianity) occasionally for church windows. It was not until the early medieval period that glass was produced, rather than simply re-worked, in Britain. Unlike the durable soda lime glass produced by the Romans, this was potash glass – so called as the sand (silica) was mixed with the ash of burnt plants such as bracken. Potash, or forest, glass survives poorly in the ground, often becoming very fragile with opaque surfaces. From the late 16th century, large glassworks were set up across Britain to produce pale green tinted lime-rich glass and, later on, the colourless lead ‘crystal’ glass.

It’s easy today to take glass windows for granted, but this small find is a reminder of how much colder (or darker) buildings were in the past. Even if you were wealthy enough to afford window panes, it was a toss up between seeing the view and warmth.

If you’d like to know more about historic glassworking, take a look at Historic England’s Archaeological Evidence for Glassworking.

Post a Comment