Humans of the Ice Age

- 3rd November 2018

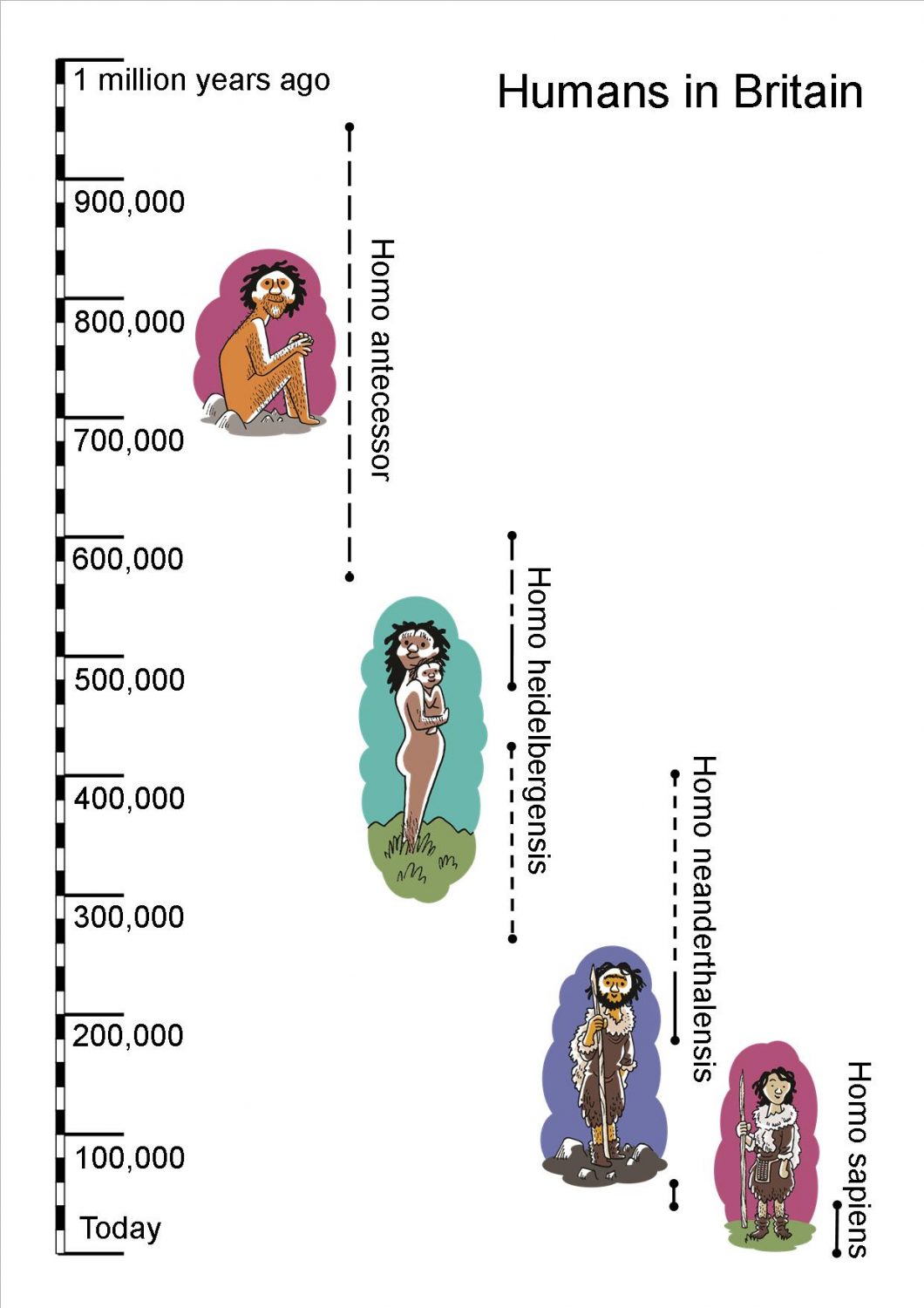

Our species evolved in an Ice Age world. 99% of the span of human life in Britain falls within the Ice Age. There have been at least four human species in Britain over the last million years. For most of human history, there have been multiple human species living at the same time. Today, we – Homo sapiens – are alone.

The earliest evidence for humans in the West Midlands dates back about 500,000 years. How can we get close to understanding our ancestors and distant cousins? Studying the lives of humans in the last Ice Age is often difficult: the organic materials that they used for tools, shelter, and clothing rarely survive across such a long span of time. Humans in the Ice Age were hunter-gatherers – they moved across the landscape lightly. But the evidence is there, hidden deep within river gravels, estuary silts, and caves.

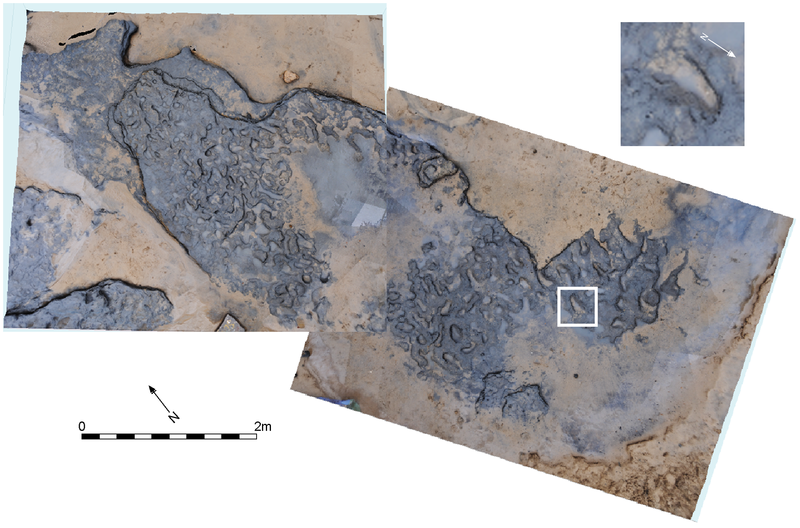

Preserved footprints on the beach at Happisburgh – taken from Ashton et al. 2014 (CC-BY-4.0)

800,000 years ago a group of early humans walked over estuarine mud flats. Remarkably, their footprints survived and were recorded on the Happisburgh coast, Norfolk in 2013. This is the first evidence of humans so far found in Britain – researchers suggest the footprints were made by Homo antecessor, a species found elsewhere in western Europe. Britain was connected to Europe by a land bridge at this time, making the journey easier for these early humans.

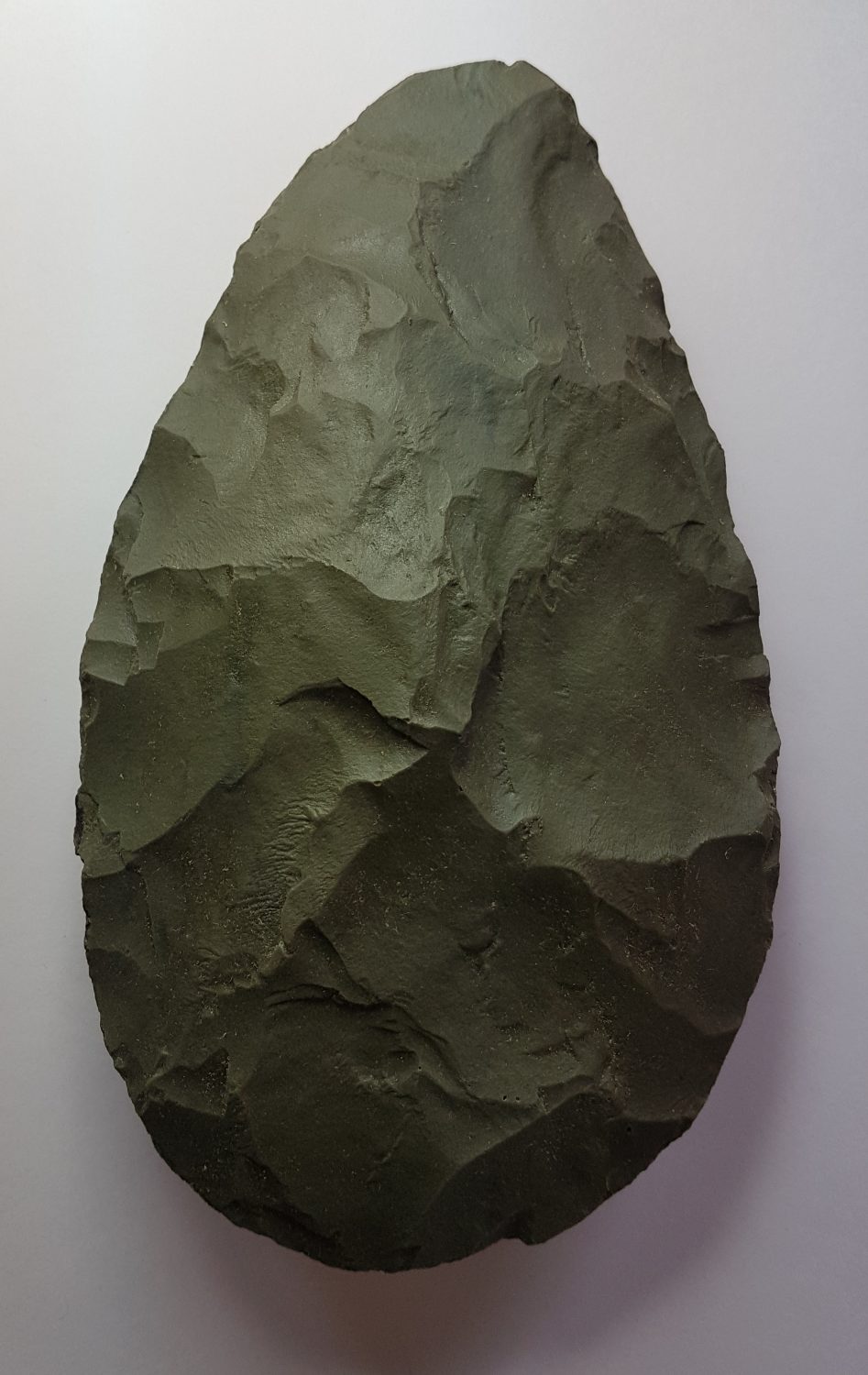

By 500,000 years ago it’s likely that another human species was living or passing through the West Midlands: Homo heidelbergensis. A group of handaxes were found at Waverley Wood, Warwickshire alongside animal remains, including straight-tusked elephants. The stone is not local and comes from an outcrop in the Lake District; it is unlikely to have been moved by glaciation, reminding us how mobile these communities were.

One of the Waverley Wood handaxes (3D printed replica)

At Boxgrove in Suffolk, Homo heidelbergensis lived alongside elephant, lions and hyenas. The stone tools they made and bones of animals that they hunted were found where they’d fallen, half a million years before. Human bones and teeth were also found; the earliest human fossils from Britain. Homo heidelbergensis have been called the handaxe makers because of the beautifully crafted handaxes they made, used and left behind.

Fast forward to 450,000 years ago and the British Isles were hit by the most extreme glaciation of the last million years: the Anglian Glaciation. Parts of Britain were entirely covered in thick ice and humans were absent from Britain for at least 50,000 years.

About 400,000 years ago a young woman died at Swanscombe in Kent. Her skull still survives, which shows characteristics of a new species – Homo neanderthalensis. Over the next 350,000 years the climate regularly switched between warm and cold and the Neanderthals came and went from Britain. Despite learning to adapt to the colder northern environment, they were beaten back from Britain several times when the climate was particularly harsh.

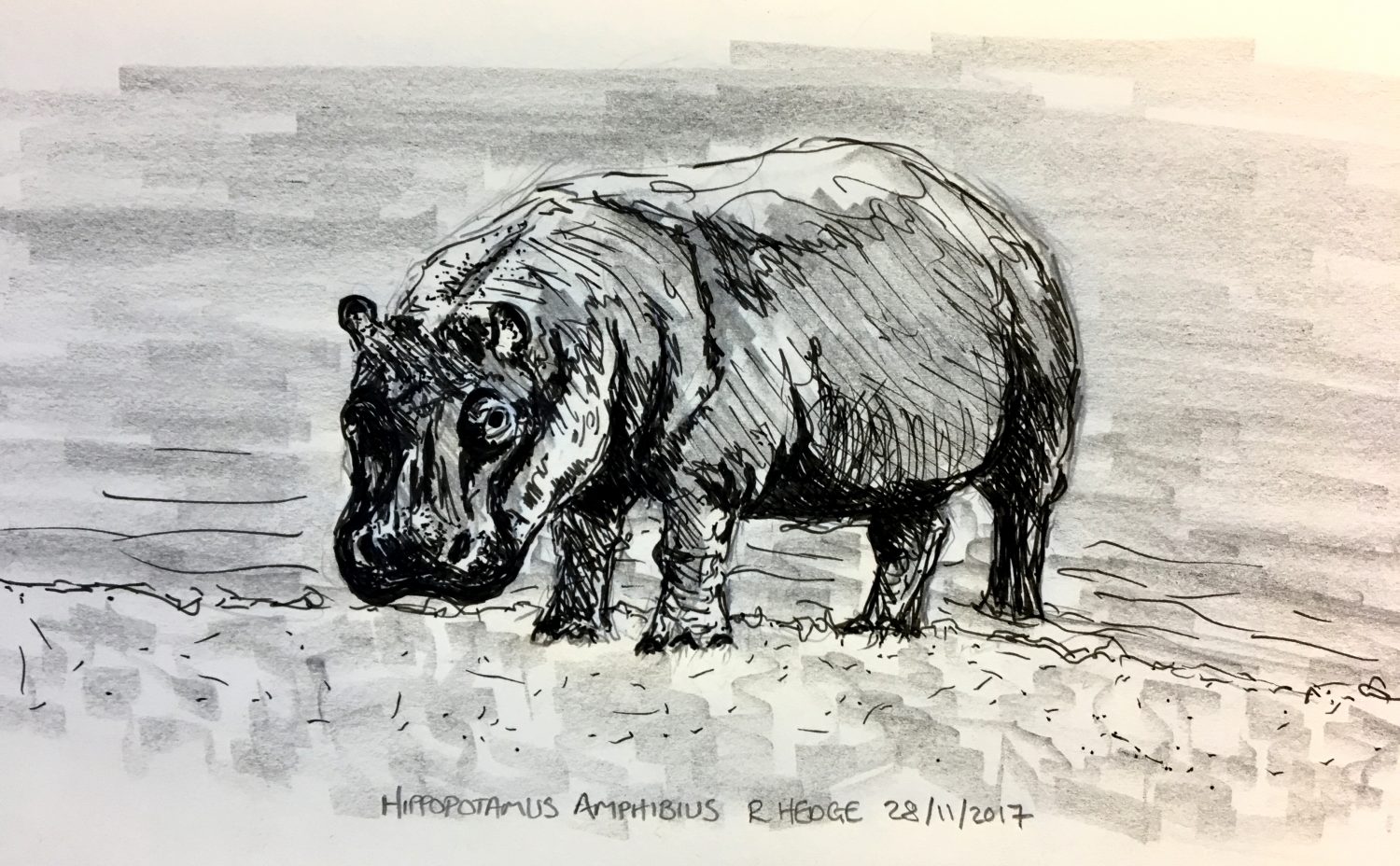

The severe cold that began 180,000 years ago forced Neanderthals out of Britain once more and this time Britain was deserted for 120,000 long years. The climate changed during this time but despite one of the warmest periods of the last half million years, Neanderthals did not return. Hippos basked in the rivers and elephant walked across the countryside without the company of humans.

Around 60,000 years ago Neanderthals returned to Britain. The climate was tolerable but still cold and sea levels so low that much of the North Sea and English Channel were dry land, allowing migrating animals and their Neanderthal hunters to travel north into Britain once more. These were to be the last of their species. They shared the landscape with bison, aurochs, bear, wolf, mammoth, woolly rhino and reindeer.

Around 45,000 years ago a new type of tool appears in Britain and its maker is still uncertain. Long blades shaped to leaf points were produced. The largest leaf point site is at Beedings in West Sussex, where leaf point makers sat at the top of a hill watching prey below and repaired their tools, replacing broken tips with new ones. Tantalisingly, these blades may have been made by the very last Neanderthals or they might the first signs of a new species, modern humans like us: Homo sapiens.

The earliest human bone belonging to our own species is a jaw fragment found in Kent’s Cavern in Devon. Scientific analysis estimates it to be at least 40,000 years old. Modern humans were highly adaptable and innovative hunter-gatherers who lived in larger groups with wider social networks. They appear to have moved over large distances sharing new ideas and knowledge.

Around 40,000 years ago the last separate Neanderthal populations died out across Northern Europe and modern humans, like us, became the only people left on the planet.

Find out more about our Ice Age past at iceageworcestershire.com

Images by Andi Watson

Superb piece of history for Britain. Thanks for sharing.