Archaeology 50: Crowngate Centre, Deansway, Worcester

- 22nd April 2020

In our series of blogs by former County Archaeologists the excavations at Deansway under what is now the Crowngate Centre came up quite a few times. This is still the largest excavation ever undertaken in the City and the findings are still significant even after 30 years. It also played a big part in the careers of many archaeologists, some of whom Victoria Bryant, Robin Jackson and Laura Templeton are still with us.

Aerial view of excavations, Huntingdon Hall in centre

The construction of the shopping centre meant that the evidence for part of historic Worcester would be lost for ever and so it had to be excavated, recorded and published. It was an amazing opportunity to delve into the city’s past. We knew that this area was part of the medieval and later city, but we were not sure what the site had looked like in the prehistoric, Roman and Saxon periods. The funding was provided by from the Manpower Services Commission (staffing), English Heritage (post excavation analysis) and the developers, Crown Estate.

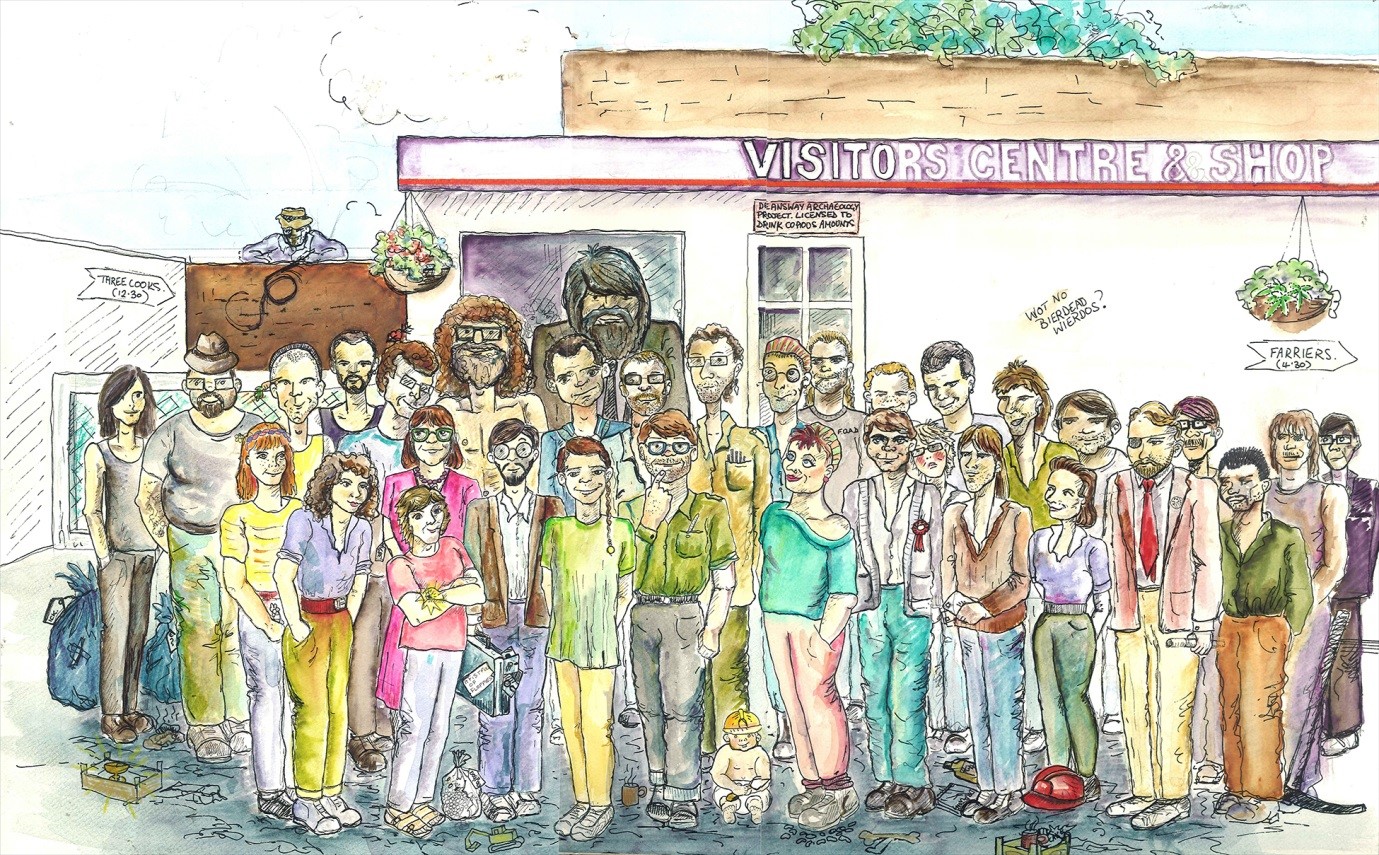

The archaeologists, drawn by Laura Templeton

The excavation (unofficially called the Deansway dig) was directed by Charles Mundy and was started in May 1988. We opened four large areas (over 1900m2) around the Countess of Huntingdon’s Chapel.

Excavation continued until December 1989. Fifty-three members of staff were involved in some capacity over those 20 months digging, recording, identifying and illustrating the finds and processing environmental samples. We were joined by lots of volunteers, many of whom were later involved in other projects for the Service. Teresa Jones, currently Senior Archives Assistant with WAAS in The Hive, volunteered on Mondays whilst she was at college and still has a Deansway Dig pencil!

One aim of the project was to encourage local people to find out what we had found through a series of public events. Being in the centre of Worcester meant we were very visible and people wanted to know what was going on. Being central also meant the archaeologists were easily identifiable as they could be spotted at lunchtime and after work covered in mud!

Excavation is what most people think when they think of archaeology, but it is only the first, and usually the quickest, part of the whole process. After the site was backfilled ready for construction of the shopping centre, the post-excavation process began.

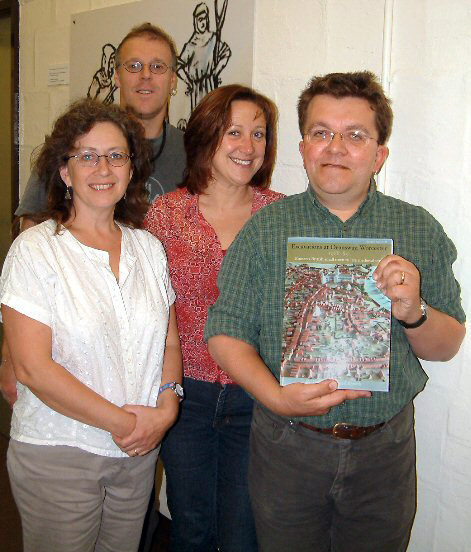

Overseen by Hal Dalwood, the paperwork, photos and plans were checked, the finds were analysed and drawn, environmental evidence looked at and many, many external specialists consulted. All this effort finally led to a very substantial report in 2004. It weighs 2.34kg (5Ib 2oz) and is available to read in our Local Studies Library at The Hive. It is still a well-used reference work as can be seen by the dog-eared condition of the copies still used by our archaeologists. The full report took some time but some of our discoveries were made available more quickly as they contributed to the panels of the Crowngate historic trail which can still be seen today.

So what did we find? The story of many centuries of Worcester’s past was unearthed. We could observe the development of this part of the modern town as it grew and then declined and grew again.

The first evidence of people passing through what is now a shopping centre are fragments of stone tools dating to the Bronze Age (c 2500 to 800 BC) but the first signs of people living on the site date to the late Iron Age (c150 BC to early 1st century AD) and include the remains of a roundhouse and a horse burial. The area was probably farmland at this time. After the Roman conquest (43 AD) people continued to live nearby and we found evidence of their rubbish including Roman pottery, glass and some lost coins. A few fragments of military equipment hinted that the Roman army was in the area.

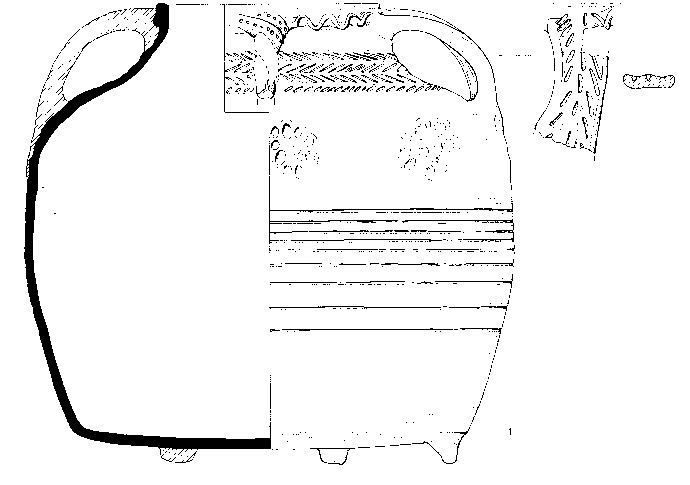

By the late 2nd century AD there is evidence that this area of the town was industrial with large scale ironworking and smelting. Iron slag, the result of the smelting, was so plentiful that it was used for the foundations of roads across the settlement. The area under the shopping centre was certainly not posh at that time. Unlike other parts of Roman Worcester (for example Sidbury) pottery used on the Crowngate site was almost all locally made for everyday use. There were less coins, hairpins, bracelets and brooches recovered here than from other areas of the Roman town.

By the 4thC AD the area was once more fields. We also found a small burial ground (the first Roman cemetery in Worcester to be excavated) containing fourteen people laid mostly north-south, nine of whom were buried wearing hobnail boots. Three bodies had been decapitated with their heads placed by their feet. Why? Other burials of this kind at this date have been found across the country but the reasons are not yet understood.

After the Roman period Worcester shrank in size and the area now covered by Crowngate was largely pasture with a few farm buildings including a large clay oven.

Historical sources tell us that an Anglo-Saxon burh (a fortified town) at Worcester was founded in the later 9th AD. Most of the area of the Crowngate excavation was outside the ramparts and palisades but in one small trench we did find the very first structural evidence of the burh defences ever recorded. Even after the Norman Conquest when the defences had gone out of use their presence effected the plots and layout of Worcester and the shadow of them remains in the modern city. Whilst the area around the defences was kept clear there was development of houses plots in the later Anglo Saxon period. These were aligned to the street which later became known as Birdport and which led to a gate into the medieval city. Birdport was destroyed by the construction of Deansway in the 20th century.

One amazing discovery dating to the Anglo-Saxon period was a fragment of a Roman, Samian Ware, bowl which had been inscribed with a runic inscription at some point in the Anglo-Saxon period. Sadly, not enough of the bowl was found to enable even an international expert to decipher the inscription.

In the medieval period the population of Worcester grew, buildings in the city became more and more densely packed and the site was inside the town defences. An urban elite was emerging, building in stone and replacing previous houses on the same boundaries. The Severn had always been an important river. In the Middle Ages it was an internationally important trade route and enabled Worcester to prosper. The parish in which the excavation occurred is St Andrew’s the second wealthiest in Worcester at that time and this was reflected in objects that we found from pottery to metal work.

The first half of the 14th C was a time of bad weather, bad harvests and famine. In 1349 the Black Death arrived in England. It is estimated that c 40 to 50 % of the world’s population died at this time. In Worcester this high death toll led to the abandonment of houses and the conversion of tenement plots to, at Crowngate, gardens and a bronze foundry. As the city’s population gradually recovered, probably helped by migration from other areas of Worcestershire, the foundry and gardens were replaced with new houses. Many of these survived until the slum clearances in the early 20th century.

After the dig

The Crowngate dig is one of the most important ever undertaken in Worcester. The size of the area uncovered meant we could really get to grips with the processes of change over time. It also allowed us to put discoveries from other sites across the city into a framework and has informed all later work. The excavations captured the interest of local people and there were high attendance figures at our open days, tours and talks. There are many people who use our services today who remember coming to see us at work at “the dig”.

Archaeologist and Roman soldier at an Open Day

The substantial funding provided by the government via the Manpower Services Scheme was to enable young people to be trained to work in a time of economic depression. Some of us were recent graduates but others had no archaeological training. We learned together and many of us went on to have long careers in archaeology.

Some of the team came to Worcestershire and never left. Victoria Bryant was Finds Supervisor for the dig and is now manager of Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service. Robin Jackson was a Site Manager and is now a Senior Project Manager. Laura Templeton who drew the cartoons for The Digger, the unofficial record of the excavations, is a Senior Illustrator.

Laura Templeton, Robin Jackson, Victoria Bryant & Hal Dalwood with the finished report

Talking about the Deansway dig brings back lots of memories to quite a few of our staff, former colleagues and volunteers. There was great team spirit which could often be observed in the local pubs, particularly the Farriers Arms in Fish St. They are very proud of the story they unearthed.

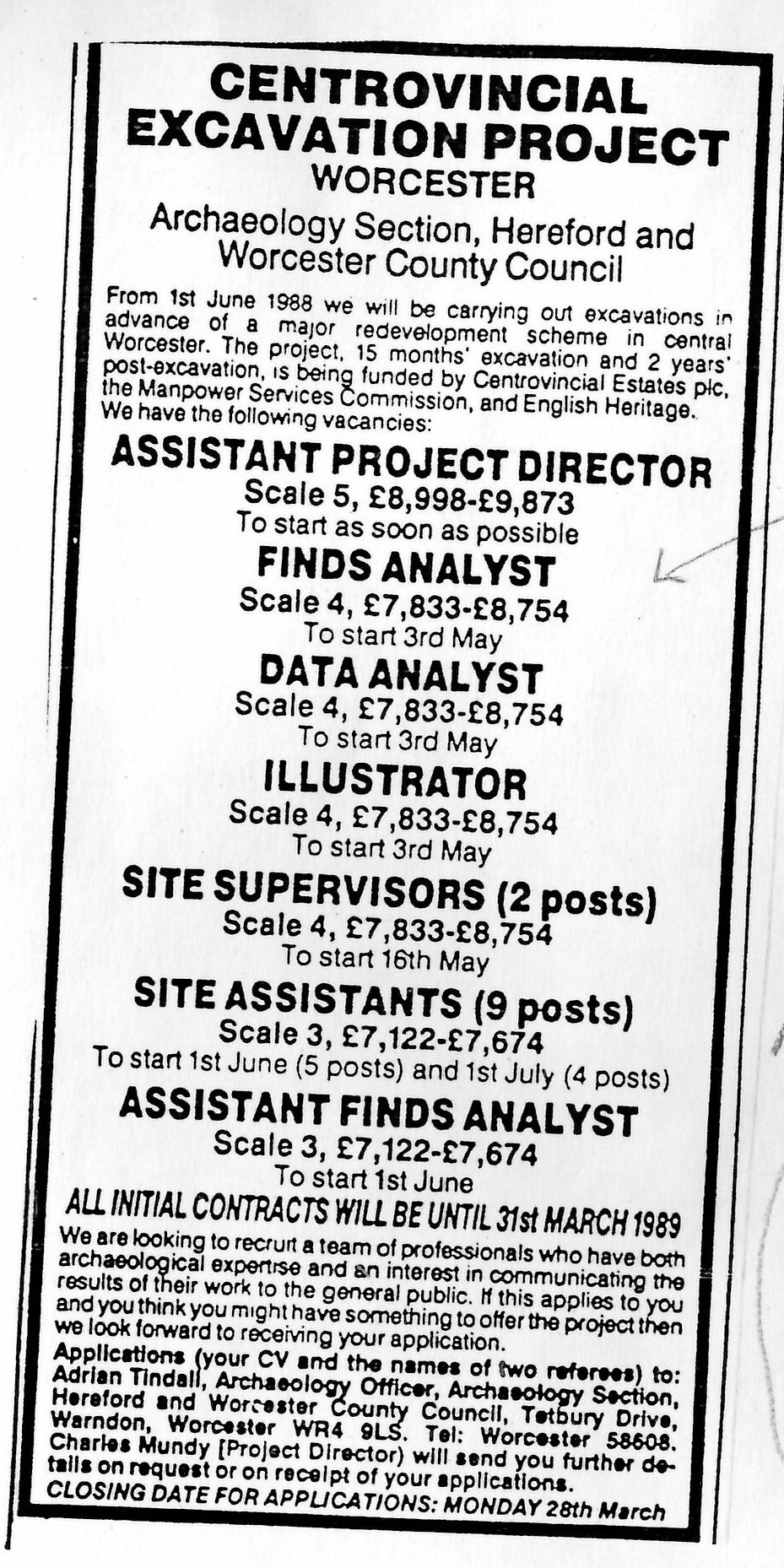

Job advert for the project. The development was originally called Centrovincial, before Crown Estates took it over and it the shopping centre became Crown Gate.

Post a Comment