Bees & The Hive

- 25th August 2021

One thousand intricately painted, hand-crafted bees are being displayed in the garden of The Hive from 20th August until 2nd September 2021 to raise funds for St Richard’s Hospice. Humans have long history with honey bees and we thought we’d take the opportunity to explore the archaeological and historical evidence of that relationship. A display is on Level 2 in The Hive until early September 2021.

Bees in the garden at The Hive

Honey bees and humans

Honey bees and humans

Honey has been used to sweeten foods and drink since early prehistory. Palaeolithic rock art in Europe and Africa shows bees and honeycombs, with some images dating from as early as 40,000 years ago. Evidence of beeswax has also been found stuck to the inside of pottery from early farming cultures in Europe, the

Middle East and North Africa, including in cooking pots from a site in eastern Turkey dating to about 8,500 years ago.

In Britain honey harvesting has been practiced for at least several thousand years. Evidence survives in the form of literature, art and archaeological evidence from late prehistory onwards. Evidence also shows that honey bees and their products held a sacred place in various myths and traditions alongside their practical uses. Archaeologically, honey has been found in ceramic vessels in the form of grave goods in Bronze Age burials. From Roman Britain there is more written evidence with, for example, references on wax tablets at Vindolanda relating to the purchase of honey. Closer to home, excavations at Roman Wroxeter in Shropshire identified a large number of honey jars, indicating that honey was in abundant supply there.

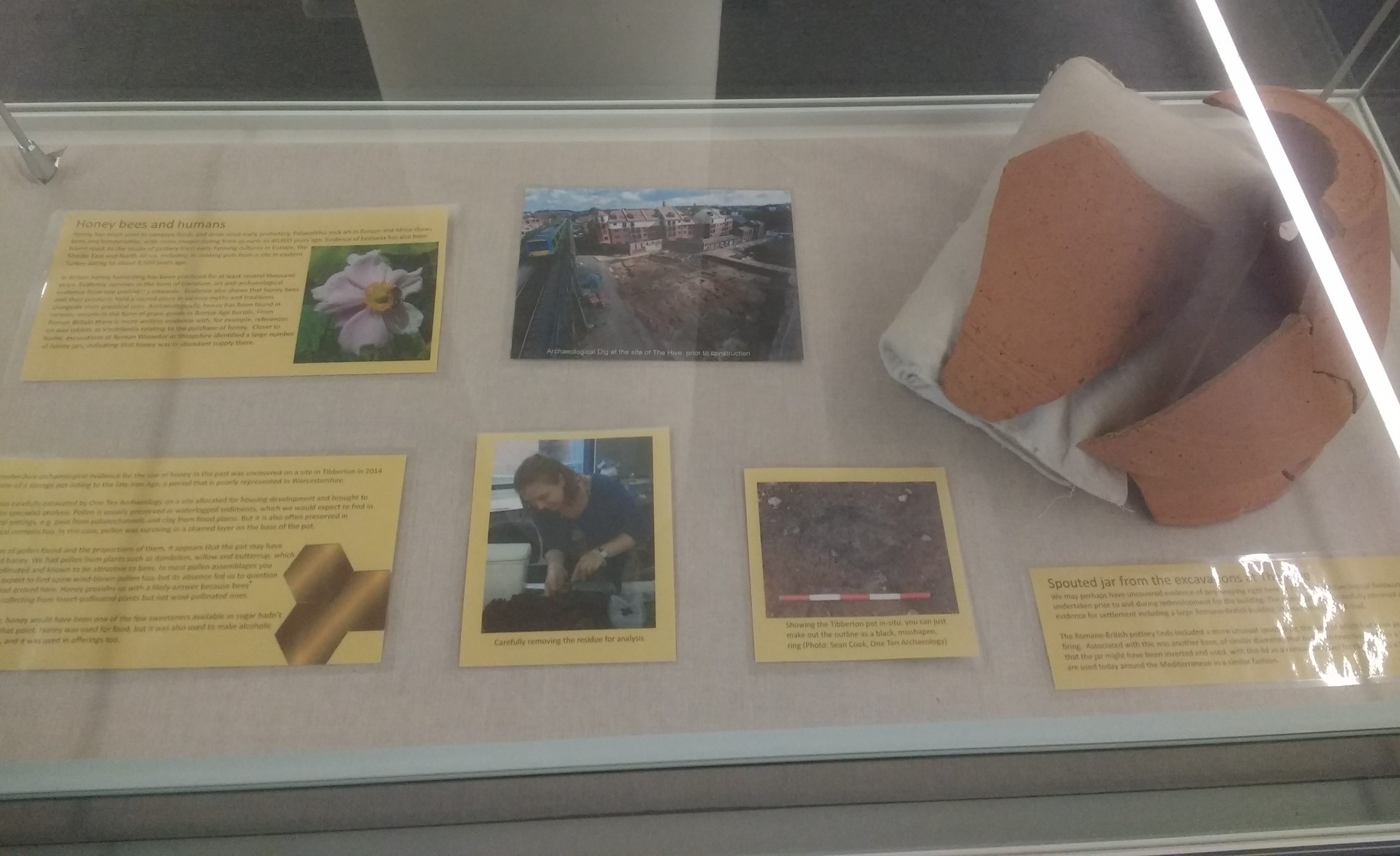

In Worcestershire archaeological evidence for the use of honey in the past was uncovered on a site in Tibberton in 2014 in the form of a storage pot dating to the late Iron Age, a period that is poorly represented in Worcestershire.

The pot was carefully excavated by One Ten Archaeology on a site allocated for housing development and brought to The Hive for specialist analysis. Pollen is usually preserved in waterlogged sediments, which we would expect to find in more natural settings, e.g. peat from palaeochannels and clay from flood plains. But it is also often preserved in archaeological contexts too. In this case, pollen was surviving in a charred layer on the base of the pot.

From the types of pollen found and the proportions of them, it appears that the pot may have once contained honey. We had pollen from plants such as dandelion, willow and buttercup, which are all insect-pollinated and known to be attractive to bees. In most pollen assemblages you would normally expect to find some wind-blown pollen too, but its absence led us to question how this pollen had arrived here. Honey provides us with a likely answer because bees would have been collecting from insect-pollinated plants but not wind-pollinated ones.

Showing the Tibberton pot in-situ, you can just make out the outline as a black, misshapen, ring (Photo: Sean Cook, One Ten Archaeology). Carefully removing the residue for analysis

During the Iron Age, honey would have been one of the few sweeteners available as sugar hadn’t arrived in Britain at that point. Honey was used for food, but it was also used to make alcoholic drinks, such as mead, and it was used in offerings too.

Spouted jar from the excavations at The Hive

We may perhaps have uncovered evidence of bee-keeping right here at The Hive. Archaeological fieldwork was undertaken prior to and during redevelopment for the building. The investigations successfully retrieved a range of evidence for settlement including a large Romano-British building situated on a cobbled road.

The Romano-British pottery finds included a more unusual spouted jar, the base of which had been perforated after firing. Associated with this was another base, of similar diameter, that had been reworked to form a lid. It is speculated that the jar might have been inverted and used, with this lid as a removable cover for the hole, as a beehive. Such pots are used today around the Mediterranean in a similar fashion.

Spouted jar found on the site of The Hive – possible beehive

The Hive excavations, during which the spouted jar was found

A skep beehive, as used in bee boles in hollows in garden walls

Beehives

From the medieval period beehives became a normal addition to gardens. Surviving examples of associated structures are often attractive and elaborate features too. Bee boles are small hollows in walls in which beehives, called skeps were kept. The bee bole helped to protect the skeps from the cold, wind and rain. A skep is a simple form of hive in use from at least the medieval period, the word probably originating from the old Norse ‘skeppe’ for basket. Made from straw, rope, hazel or willow they were sometimes covered in mud or cow dung to protect them.

The IBRA Bee Boles Register lists a few houses in Worcestershire with surviving bee boles from the 19th century or earlier, but none are publicly accessible. Fine examples in the midlands include those at Packwood House, a National Trust property open to the public.

Flowers and Pear Trees outside The Hive

Bees in Worcestershire

In common with the rest of the UK, and indeed the planet, Worcestershire has suffered huge losses of natural habitats and species. In October 2015 Worcestershire County Council declared itself a ‘pollinator-friendly’ county. Part of this commitment includes the implementation of the Worcestershire Pollinator Strategy. The strategy is an initiative to increase native flower-rich habitats which help support insect pollinator populations, including honey bees, which are currently in decline nationally and globally. It is part of the 2018-2027 Worcestershire Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) which identifies 17 habitats and 26 species, or species groups, which are of particular conservation priority in the county.

You may have noticed areas of wildflowers brightening up verges and open spaces across the county, including at County Hall. The wildflowers around The Hive are part of this commitment to support our native insects.

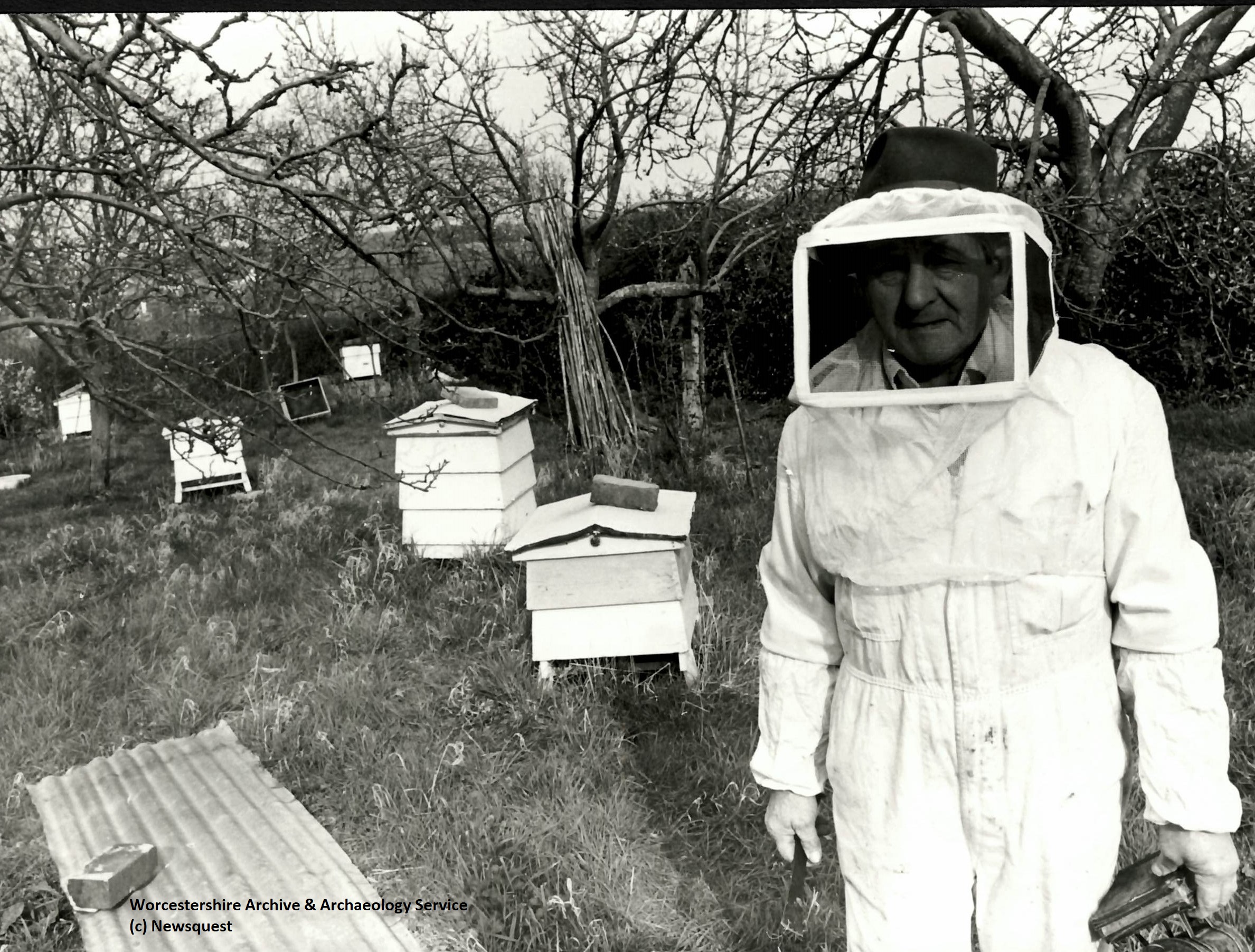

Tom Griffiths, bee keeper in Broadwas 1981, from Worcestershire Photographic Survey. Copyright Worcester News

Programme for 15th Annual Convention of Midlands & South Western Counties Convention of Bee Keeper,s 1935. From Worcestershire Archives.

You can see the display on level 2 in The Hive until early September 2021

Bee bibliography

Bradley, R. Evans, C J. Pearson, E. Richer S. and Sworn, S. 2018. Archaeological excavation at the site of The Hive, The Butts, Worcester. Worcestershire Archaeology Research Report No. 10

Cook, S. 2015. Land (Hillside) adjacent to Hawthorn Rise, Tibberton, Worcestershire. One Ten Archaeology, see also Treasures from Worcestershire’s Past: ~44~ Honey in an Iron Age pot

Crittenden, Alyssa. (2011). The Importance of Honey Consumption in Human Evolution. Food and Foodways. 19. 257-273.

The Stone Discs of Late Roman Wroxeter: An archaeology of kitchen paraphernalia

Ransome, Hilda M. 1937. The Sacred Bee in Ancient Times and Folklore. London: George Allen & Unwin

Roffet-Salque, M., Regert, M., Evershed, R. et al. Widespread exploitation of the honeybee by early Neolithic farmers. Nature 527, 226–230 (2015).

The Gardens Trust. The buzzing of the bees….. Accessed 13/08/2021.

Worcestershire County Council 2018. Worcestershire Biodiversity Action Plan Biodiversity Action Plan | Biodiversity Action Plan | Worcestershire County Council

Worcestershire County Council 2015. Worcestershire Pollinator Strategy Worcestershire Pollinator Strategy | Worcestershire Pollinator Strategy | Worcestershire County Council

Post a Comment