Wichenford’s Big Dig

- 17th March 2023

In April 2022, 20 test pits were excavated across Wichenford village, to the north west of Worcester, as part of the Small Pits, Big Ideas project. Quite a lot is known about the history of the village through documents we hold in the archives at The Hive, but what material evidence of medieval occupation could we find?

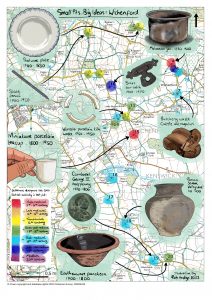

Summary of Wichenford’s test pits, showing the earliest settlement activity found and a selection of finds (created by Rob Hedge)

This community excavation was part of a wider project – Small Pits, Big Ideas – researching rural medieval settlements across the county. Together, these test pits tell a broader story of the village over time. Today our household rubbish is taken away regularly, but in the past rubbish was often thrown out the back of houses. This wasn’t just food waste, but broken pots, bits of building rubble and anything else that was old or broken. Back gardens are therefore an ideal place to look for clues. Pottery can be easily dated, as fashions for different styles changed over time. The amount of pottery found in a test pit can give us a rough idea of how nearby people lived at different times in the past.

What is a test pit?

Test pits are mini excavation areas, just 1m by 1m. They are dug in 10cm layers (called ‘spits’) with the finds from each spit kept separately, so that it’s known how deep down they were found. Test pits were mostly excavated down to the ‘natural’, which is the point at which archaeology stops and undisturbed geology begins. In Wichenford this was slightly shallower than expected and generally 30-50cm below ground level.

What do we already know about the village?

Wichenford Local Heritage Group is very active, and they have been researching the history of the village for many years. Thanks to them we know quite a bit about the early settlement of the area, going back to before the Norman Conquest. The village is not mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 but in 1095 chapels in both Wichenford and nearby Kenswick are mentioned. These were both rural parishes of the mother church, St Helen’s Worcester. This suggests that the area was populated to an extent to which two chapels within a mile of one another would have been necessary.

Bishop’s records of the 12th and 13th centuries contain early versions of names that remain familiar in the village today, such as Lingens Farm, Ruggs Place , Ridgend and Cockshut. Many of these early settlements are moated, at Kenswick, Woodhall, Woodend, Cobhouse, Colketts, Cockshut and, of course, The Court. References to the medieval village can also be found in Lay Subsidy Rolls (public tax records) in the 13th and 14th centuries,

Recent mapping around the area of Venn Lane seems to show that Wichenford had both open countryside with moated farmsteads and small nucleated areas of settlement with open fields farmed in common around Venn Lane.

Digging in test pit 20 – Photo Credit: Julie Clarke

So, what did we find?

Considering the well documented evidence of early settlement in the area, the biggest surprise was the distinct lack of medieval finds! We were able to dig test pits at four of the seven moated sites, and were hopeful we would find quite a lot of medieval material. However, there were only a handful of sherds of medieval pottery, of which the earliest was the rim of a 13th-century cooking pot. It’s a bit of a mystery, though we do have some thoughts as to why this might be. It could be that the moated sites were not occupied at first, having been built to impress rather than for regular habitation, or perhaps the heavy clay-based underlying geology of the area just made it very difficult to find artefacts. What seems most likely though is that Wichenford had a different land management style to other villages we have investigated, with rubbish from households being spread over fields rather than near to houses.

Despite the lack of medieval material, there were a number of later finds that can tell us more about Wichenford’s history. Small quantities of pottery show activity through the 16th and 17th centuries, before a marked increase in finds broken and discarded during the 18th century. This reflects both the expansion of the settlement and the increased affordability of consumer goods, especially once refined, mass-produced earthenware pottery became available in the mid-18th century.

Brick and tile fragments found in the southernmost test pits date back to the 16th century and probably reflect more safety-conscious residents of the village adding brick chimneys to their timber dwellings and the presence of small fingerprints on a piece of handmade brick suggests that local children lent a hand.

The finds give a snapshot of life in Wichenford over time and inevitably, they also raise further questions.

Digging and checking for finds in test pit 19 – Photo Credit: Julie Clarke

Counterfeit coins

What was very exciting was the discovery of two counterfeit Georgian coins, halfpennies of George II in test pit 20 at Lingens Farm dating from 1740-1806 and of George III at test pit 19 at Lingens Cottage dating from 1770-1806. Counterfeit bronze coins were widespread in Georgian England. Official farthings and halfpence were in short supply when mint production ceased in 1725-8, 1755-69, and 1776-96, and there was also a rising demand for lower value coins to pay wages payments and transactions in towns and villages as the Industrial Revolution progressed. Interestingly, most counterfeit coins in English circulation were made in Birmingham, using equipment and techniques borrowed from the local button industry.

We know that the circulation of counterfeit bronze coins was well-established in Worcestershire by the mid-eighteenth century from newspaper reports of the time. In 1750 the Mayor of Worcester, Samuel Parkes, published a notice in The Worcester Journal (10 May 1750, 3) complaining about the ‘great numbers of base and counterfeit halfpence…[which] continue to be daily utter’d in and about this City’, and threatened to prosecute retailers who accepted them in payment. The examples found at Wichenford are important as they give a glimpse of this currency in circulation, and show how widely counterfeit coins were used beyond the major towns and manufacturing centres into the surrounding countryside.

Counterfeit halfpenny of George III found in test pit 19 |

Illustration of counterfeit halfpenny of George III found in test pit 19 |

Counterfeit halfpenny of George II found in test pit 20 |

Want to know more?

Keep an eye out for the full report on Wichenford’s Big Dig, which will be available from our website soon. You can also watch a talk below, which was given to the village in February 2023.

Post a Comment