Unpicking a Sticky Situation

- 19th September 2017

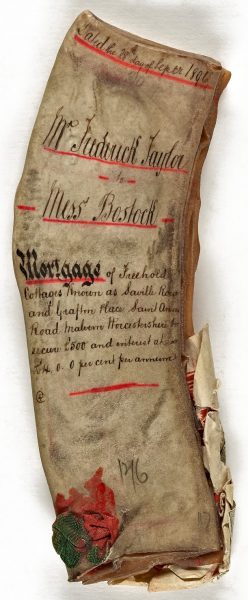

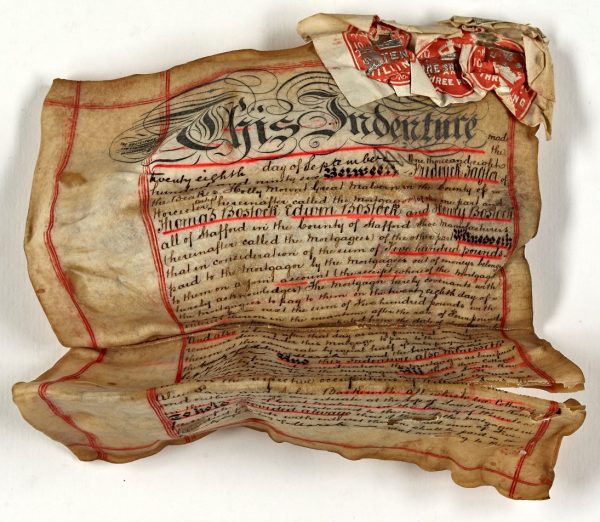

As the Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service Book and Paper Conservator, I was recently contacted by a local organisation with a bit of a problem in some of their archives. A small number of parchment documents had been discovered that were very dry and hard, and impossible to open. Looking more like the dogs raw-hide bone than a document, it seemed likely that the items had been subjected to both moisture and heat at some point in their past, causing the parchment to both stick to itself and shrink.

|

|

Document prior to treatment – hard, rigid and stuck together.

Parchment is a general term used to describe animal skin that has been removed from the animal, de-haired, stretched when wet and left to dry under tension. This causes the overall surface area of the skin to remain the same but the fibres within the skin realign and ‘glue’ themselves together in the new arrangement. As long as the material stays dry, the fibres will remain stretched, providing a strong and durable surface for writing or drawing. Generally, production methods have changed little throughout the use of parchment.

The first mention of documents written on skins can be traced back to Egypt in about 2700BC. Widespread use was replaced by paper during the late 15th century due to the advent of printing which increased demand to the extent that parchment production was unable to keep pace.

The terms ‘parchment’ and ‘vellum’ are often used interchangeably, but in fact, ‘parchment’ correctly refers to the dried skin of a sheep, calf or goat, whilst ‘vellum’, derived from the Latin word vitulinum meaning “made from calf” refers specifically to calf skin.

Unlike in the production of leather during which the tanning process causes the proteins in the skin to undergo a chemical reaction, parchment production involves no chemical reaction, just the stretching and drying of the skin. As a result, parchment is a hard, inflexible material that when wet, will revert to its original shape (‘sheep-shape’) and can putrify, whilst the tanning process produces a flexible product that does not putrify when wet.

This is what had happened to the document I was presented with. It is likely that at some point it had been exposed to moisture which caused the document to soften, then to shrink and stick together when subsequently exposed to heat. The document was now small, hard, brittle and firmly stuck together.

Despite this, I was confident that with careful humidification and manipulation, I would be able to introduce just the right amount of moisture to soften the parchment and allow it to be opened and read again, though the extent of this would depend on how much time and money it was felt worth spending on the document, and sadly, success may not be guaranteed.

In the end, it was decided to spend an hour of my working time on the document to see what success could initially be achieved. The document was wrapped in moistened ‘Sympatex’ and dampened felt then sealed in an improvised humidity chamber to maintain a moist environment, with periodic checks on progress. The trick was to introduce just enough moisture to allow the parchment to become malleable without introducing too much to result in further degradation and damage to the document – an exercise in patience as ‘picking’ at the document before it was sufficiently softened would result in further unnecessary damage.

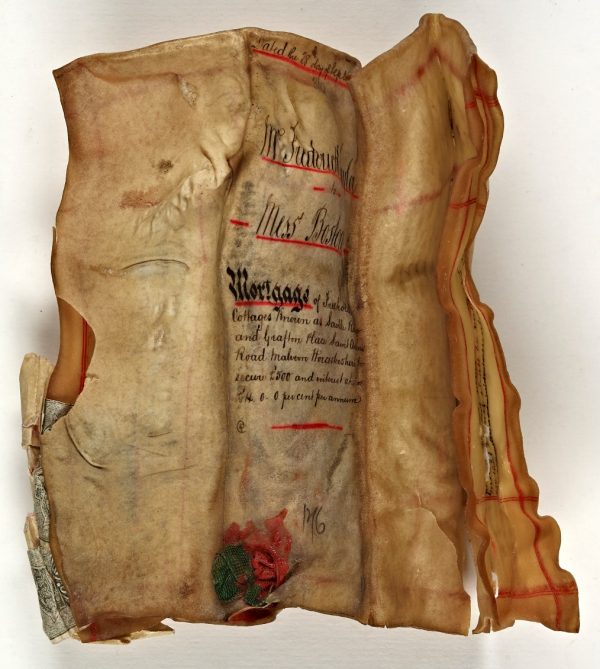

Document following treatment – still hard and rigid, but slightly less stuck together.

Following the treatment, it was possible to open out the document only to a limited extent, and the document remained hard and brittle. It is likely that continuing treatment for a longer period would provide improved access and increased handling properties, but for now, this was all the client wanted to undertake. For me, it was a fun exercise to work on a document that was on the verge of being inaccessible and to bring it back from the brink, and to see that more could be done with time and a lot of patience!

If you would like to would like to enquire about potential work our Conservation service can carry out, please submit an enquiry online and we will get back to you.

Post a Comment