Birmingham Buttons – Find of the month

- 1st October 2019

We went looking for a Roman Road and all we found were buttons!

In a scruffy corner of an old sports field in Perry Barr, RPS Group asked us to dig some trenches to look for remains of a Roman Road which once passed beneath the proposed location of a new school. There was little left of the ancient routeway beyond remnants of the roadside ditches. But the area had been levelled with a dump of curious waste. It gives us an insight into industrial Birmingham: the workshop of the world.

Birmingham Buttons

Birmingham was a major centre in the production of pearl buttons from exotic seashells, which were cut and finished by hand in small workshops across the city. According to a Victorian account of the industry (Turner 1866), the fragility of the material and the skill required in the manufacturing process meant that the making of pearl buttons could not be mechanised. In 1866, the industry still employed around “2000 pairs of hands”, “assisted by nothing but the foot-lathe”. The finest ‘Macassar’ pearl oyster shells were named after a port in South Sulawesi, Indonesia. They were highly prized, and cost up to £160 per ton (equivalent to £20,000 in 2019 prices); the lowest-quality shell fetched just £20 per ton. In 1859, Turner reports, 1800 tons of shell were imported, with a value of around £66,000 (over £8 million in 2019 prices).

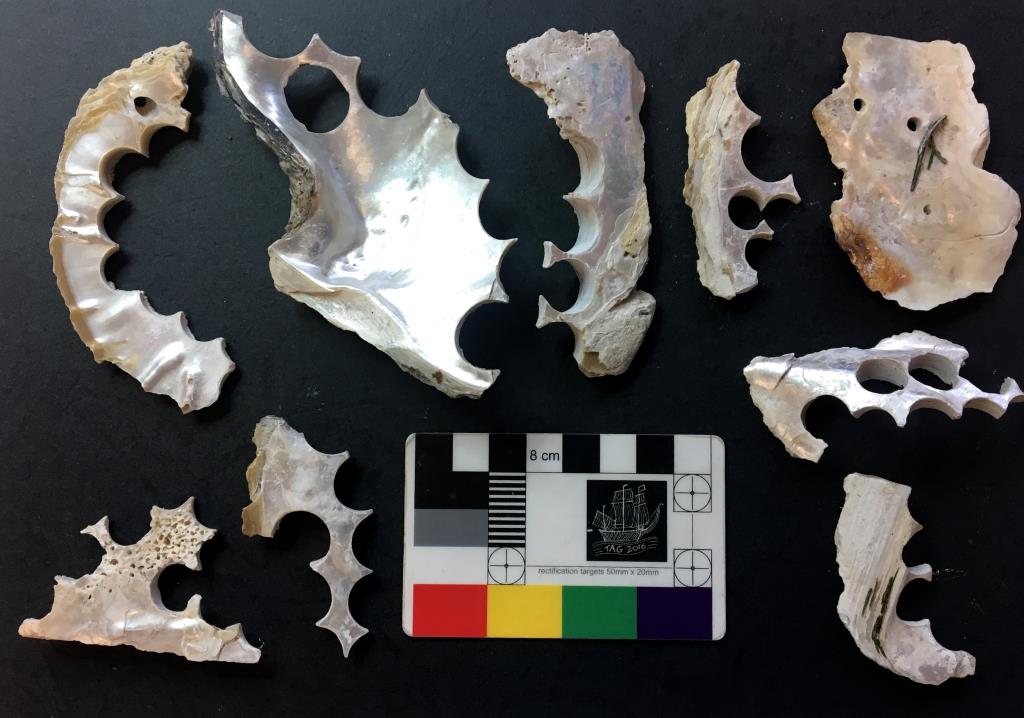

Pearl oyster shells, drilled for buttons. Seaweed clinging to shells on right of picture

The industry was centred around “a multitude of small makers”. Most workshops employed fewer than 50 people. Delicate and costly raw materials needed skilful hands, and the pearl button makers could earn a decent living. At the top of the scale, Turner records that some earned up to £4 a week. For comparison, that is equivalent to the earnings of a newly-commissioned junior officer in the British Army. But the average wage was lower: around 25 shillings a week, roughly double that of a farmhand. Women, despite doing much the same work, could only expect to take home a third of that amount.

Many of their products were destined for overseas markets, especially the USA: an export slump caused by the American Civil War temporarily depressed the industry. The development of synthetic buttons in the inter-war period triggered the decline in the pearl button industry, but Board of Trade records show that the government was still concerned about overseas competition in the mid-1930s: documents in the Qatar Digital Library include instructions to the British Political Agent in Bahrain, asking him to report on the Indo-Pacific trade in shell for button-making.

A Global trade

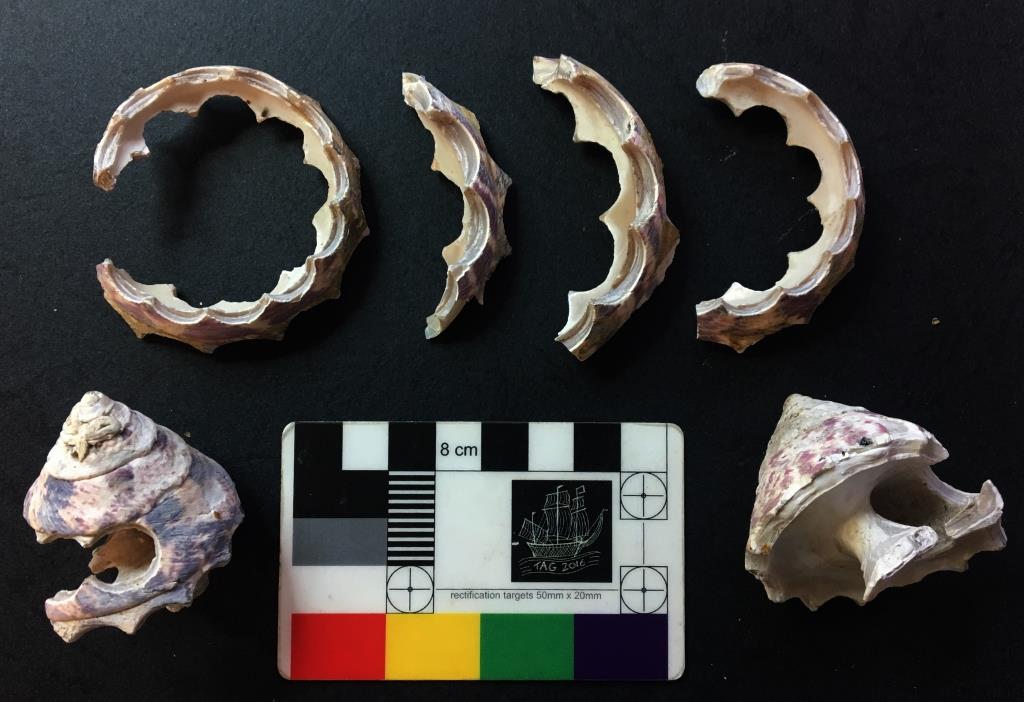

Our buttons were mostly made from pearl oyster and commercial top shell (Tectus niloticus), native to the Indo-Pacific region. Top shell was particularly popular in the early 20th century. Several of the blanks show the characteristic pink-and-white mottling of the top shell. However, the ‘Macassar’ pearl oyster and a variety similar to the ‘black shell’ described by Turner are also present. Tiny strands of seaweed still cling to some of the shells.

Indo-Pacific top shells, drilled for pearl buttons

How were they harvested? Records are hard to find, but in the 1970s, scientists from India’s Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute investigated top-shell collection by free-divers in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands:

“Shells are collected from a depth ranging from 6-13 fathom (roughly 11 to 23 metres) by skin diving. The divers… know the rich shell beds in the coastal area and collect the shell during low tide, especially from the mangrove area… divers reach the shell beds by means of dinghy called Sampan or Bonga dongi… in each, 10 adults will be engaged. Such a unit will be able to collect about 100 shells a day. The main fishing season begins by January and lasts till July.” K K Appukuttan 1977

A local industry

We found a variety of sizes and styles of button. Some are unfinished, abandoned because of an unseen flaw. Others are ‘wasters’ that shattered during manufacture. The outer surface of some had been gently heated prior to drilling, probably to render them easier to work. There are also 3 fragments from delicate decorative buckles. Their general appearance — and the types of shell used — suggest a date range between 1870 and 1940, most probably centred in the early 20th century.

Broken and unfinished buttons and buckles

Perry Barr began to grow as an industrial suburb in the latter part of the 19th century. The nearest button-maker we’ve been able to trace so far is the Regal Button Works Ltd, Grosvenor Road, thought to be situated about 1km to the SW of the site. The Regal Works was a large organisation producing a wide range of buttons, but their advertisements do not mention pearl buttons. Given the small-scale nature of the pearl button industry, it is perhaps more likely that the waste came from a smaller workshop that we’ve not yet tracked down. There’s nothing marked on historic maps of the site, so the material might have been transported from a workshop elsewhere in the city. If you know of any Perry Barr button-makers, we’d love to hear from you!

Archaeologists aren’t just interested in the factories, machines, and cogs of industry: we try to understand the social world of the workshop. Small-scale production was crucial to the importance of the West Midlands during the industrial revolution: innovation driven by groups of craftspeople in a workshop system.

What a story these little buttons tell! A story of human skill and ingenuity: a journey that began with a free-diver fetching fabulous shells from 20 metres under the sea. Ships carried them 10,000 nautical miles to a Birmingham workshop, to be transformed into beautiful buttons. Some travelled another 4000 nautical miles across the Atlantic to the wardrobes of the USA. But these little buttons never made that final step, and have lain for the last century in a field in Perry Barr.

by Rob Hedge, Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service.

Acknowledgements

Worcestershire Archaeology would like to thank Susana Parker of RPS Group, who commissioned and managed the work.

Sources

Appukuttan, K K, 1977 Trochus and Turbo fishery in Andamans. Seafood Export Journal, 9 (12): 21-25

Turner, J P, 1866 (reprinted 1967) The Birmingham Button Trade, in S Timmins (ed), Birmingham and the Midland Hardware District, 432-451. London: Frank Cass And Company. Available to view at The Hive

This was really interesting. I have always loved pearl buttons and to know more about how and where they were made was an eye opener. Thank you.

What a brilliant blog! There appears to be a long history of pearl button workers in my husbands family. Records suggest that they moved from Stratford-upon-Avon to Birmingham in the mid 19th century. Records (1851-1901 census) show that both men and woman were employed in the industry as Markers, Turners, Cutters (the men) and Finishers (the woman, who often worked from home). They lived in Moorsom Street, Aston, which is a short distance south of Perry Barr.

Wow, good to hear! The mid-19th century was the boom time for the pearl button makers. Lots seem to have lived in Aston and Lozells. I’ve heard accounts from people who grew up in that area in the mid-20th century, recalling finding and playing with button waste on rubbish tips and building sites! R.

Playing with the buttons in my mum’s button jar was one of my favourite games as a kid (and that was in the 80s)The delicacy and craftsmanship of them mesmerised me and they were never thrown away!

An interesting post. If you haven’t done so already it may be worth checking in The Birmingham Pearlies: an account of the Pearl Shell Industry in Birmingham from the 18th Century to the present day (by Sue Perfect, 2001) to see if there are any works mentioned near to the site. (There is a copy somewhere within Worcestershire libraries, though not in the Hive.) George Hook (who is Sue Perfect’s brother) still runs a small-scale pearl workshop in Smethwick and also gives very entertaining talks on the Mother of Pearl/Button trade in Birmingham (see http://www.hook-motherofpearl.co.uk/page2.html)

Thank you! A quick hunt suggests there’s a copy in Redditch, we’ll track it down. There are a few more trade directories we need to check, too. I didn’t know about George Hook, delighted to hear there’s still a small workshop running! R

About 17 years ago I went to visit the workshop of the last pearl button manufacturer in Birmingham. His name was G. Hook and he said that he intended to give up the workshop and just do talks for WIs etc. He was a fascinating speaker and many artefacts relating to the trade.

What an interesting article

Like many I have started to explore my past and surprised to discover my great grandmother came from Birmingham and the family were Pearl Button Makers and turner’s

They Moved to Bow in East London I believe …still researching

Thank you for this info

Interesting read. I just discovered my gg grandfather was a pearl button maker in the 1830’s in Birmingham.